Steve McCurry

In the Shadows of Mountains

Steve McCurry

In the Shadows of Mountains

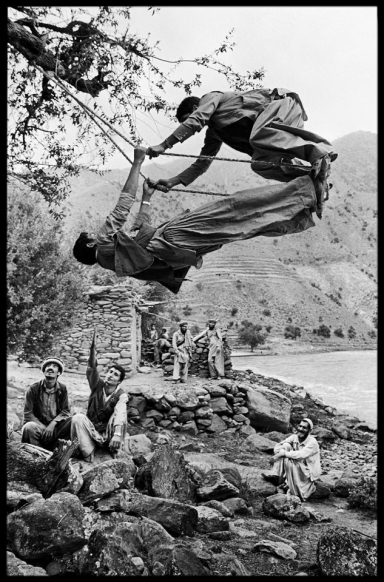

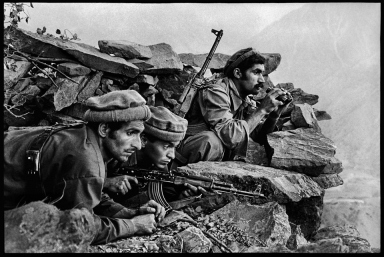

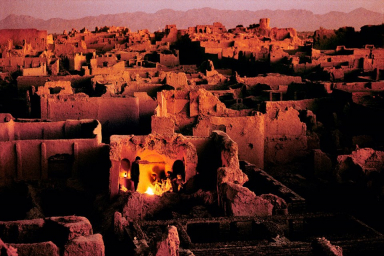

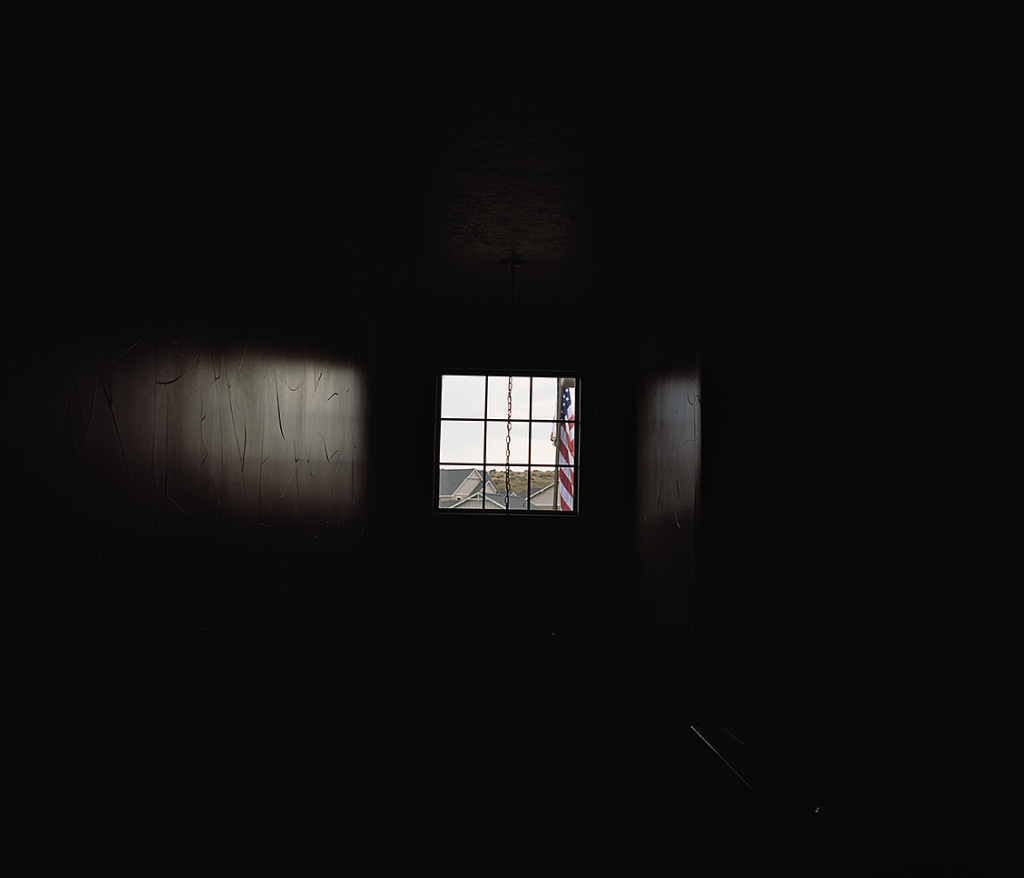

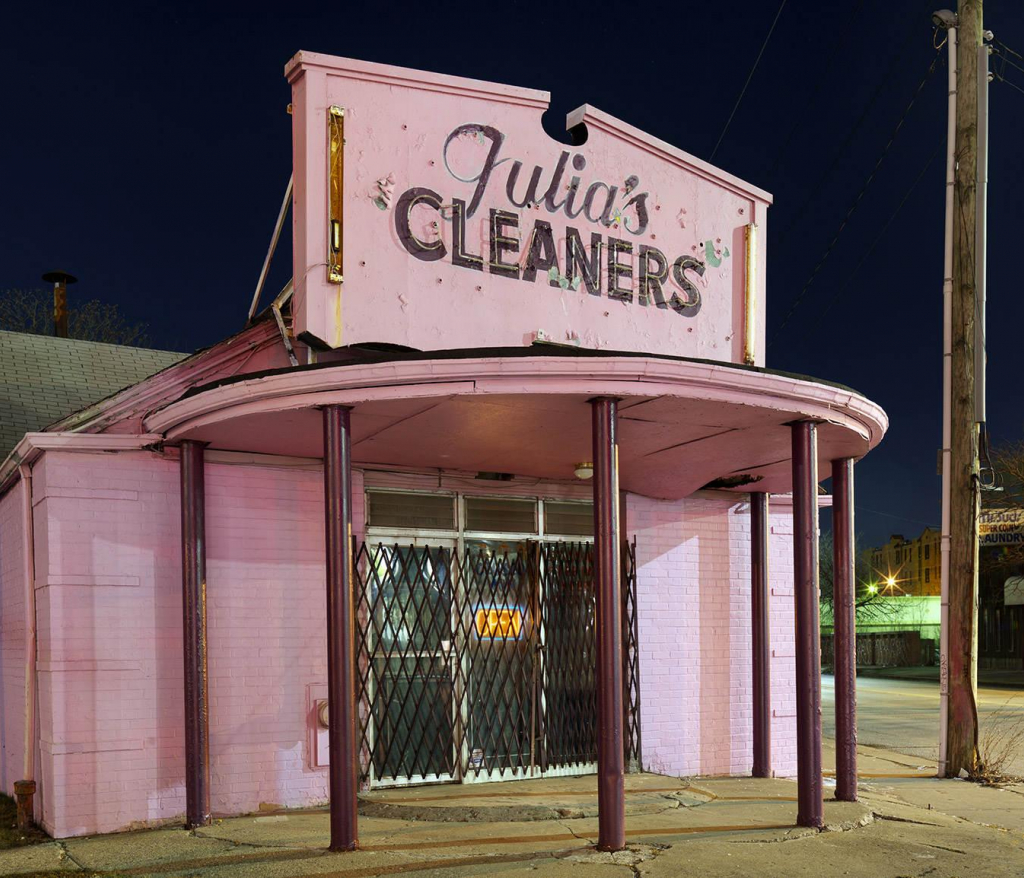

McCurry’s Afghanistan may not be the Afghanistan we are expecting. His photographs have the capacity to erode one-dimensional assumptions about the country, allowing the land to be seen in its complexity. We are welcomed into the scene and are surprised by its beauty, even in moments of violence.

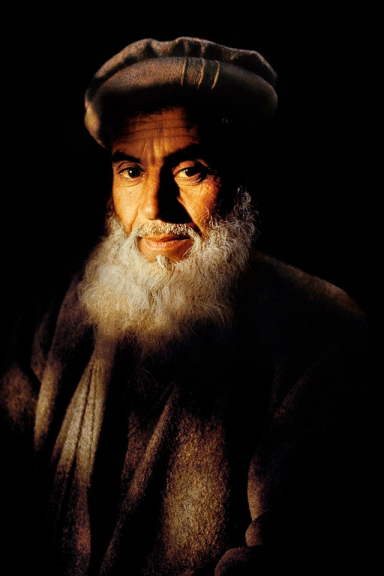

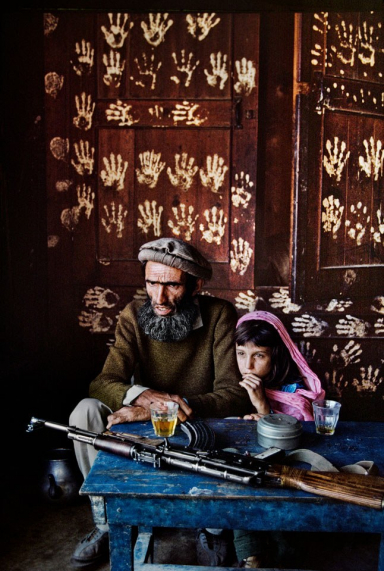

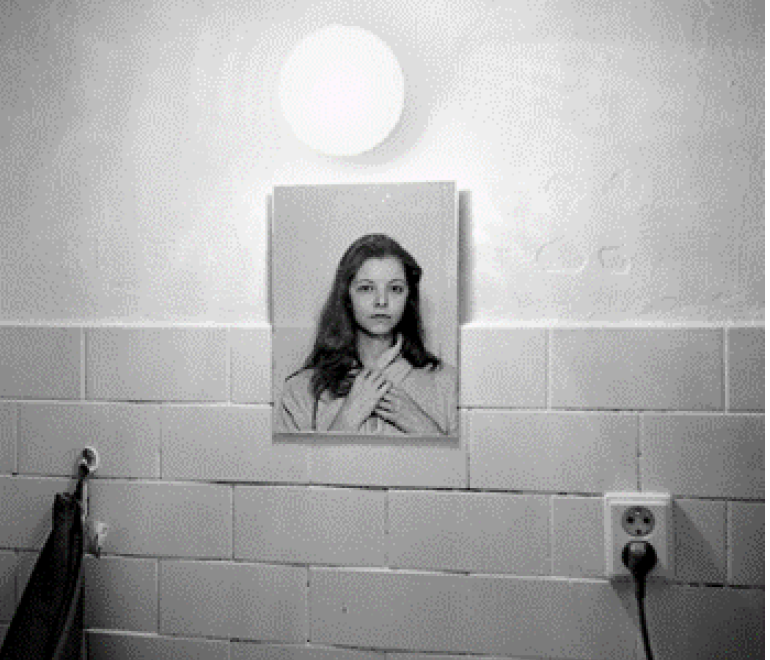

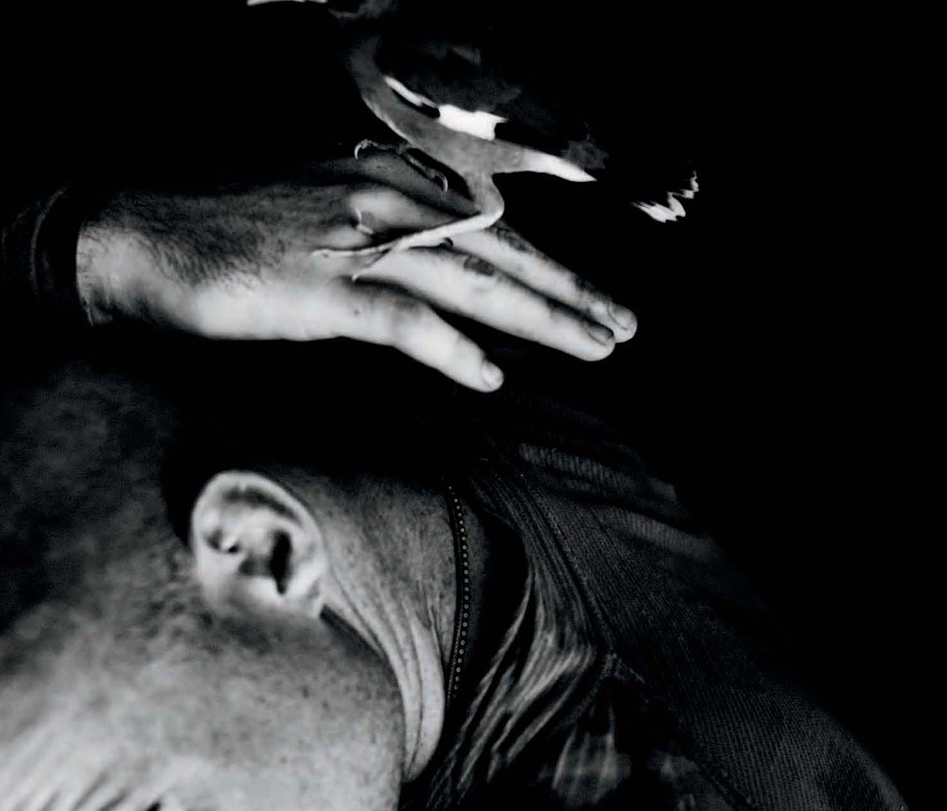

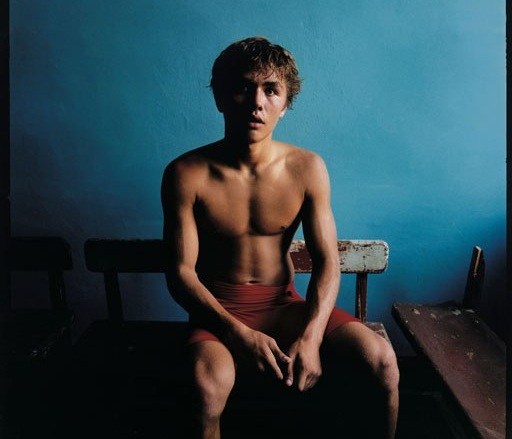

McCurry’s intimacy with a place is translated to an intimacy with the people. He is able to capture an intense gaze that draws in the viewer, however, there’s much to gain from the surrounding details as well. He manages a simplicity, or rather, a lack of excess in his composition. And yet, the images are packed with meaningful details, with economy of language. The coal miner’s fingers part for a smoke, yellow fingernails, shirt opened to the air, coal everywhere except the creases on his face. Does he scrunch his forehead the entire time he’s working? Can one smoke in the mine? Presumably not. This moment, heavy with soot, represents relief?

Along with his gifts for atmospheric conveyance, McCurry offers portraiture on a different plane. His images are often minimal but specific, and he only includes the details that matter. The nucleus of each photograph is a point of emotional resonance. It’s no accident that his photographs are seared onto our minds.

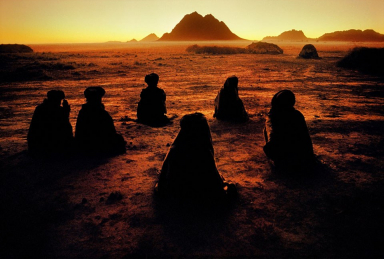

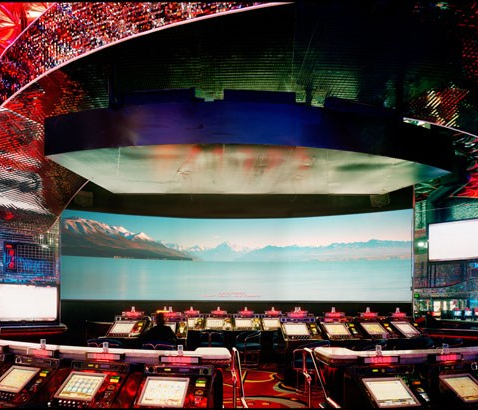

Much as outsiders try to reform it, Afghanistan never really changes. It has absorbed blows for millennia, but always continues on as before, defiantly outside of time as we know it. Without even trying, Afghanistan changes everyone who spends time there.

Afghanistan is pastoral and chaotic, peaceful and violent, destroyed and resilient, wonderfully welcoming yet deeply inhospitable.

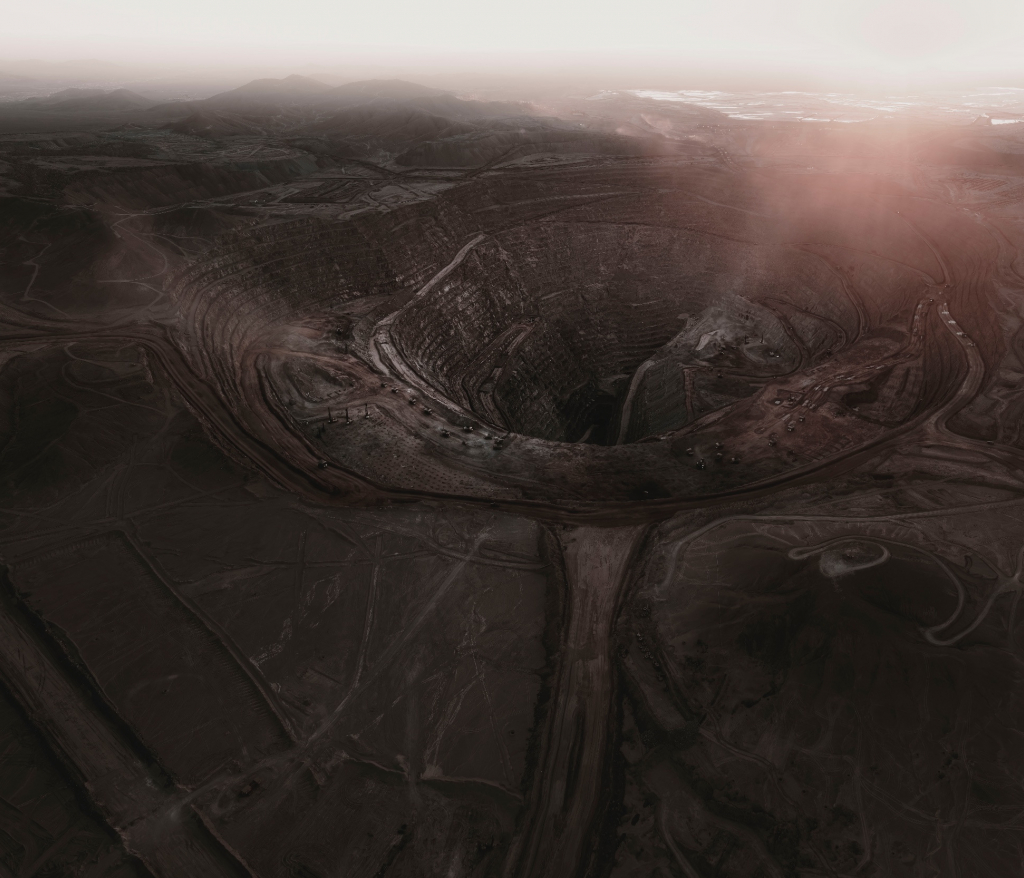

My Afghan fixation is the story of many journeys. It began in 1979, the year the Russians invaded. Twenty-nine at the time, I had travelled the world, but whatever I had done by that point was no preparation for Afghanistan, especially during a time of war. There was none of the usual military or journalistic structures. There were no seasoned colleagues, armored vehicles or two-way radios.

I slipped across the Pakistan border, following two guides who didn’t speak a word of English. My gear was inadequate; it consisted of a plastic cup, a Swiss Army Knife, two camera bodies, four lenses, a bag of film, a stash of airline peanuts and a soggy copy of Hermann Hesse’s Narcissus and Goldmund that a trekker had left in a $2-a-night hotel.

Over the next weeks, I felt like a lost dog, led by one guide or militia, then another. We moved at night, on foot and on horseback, communicating in sign language and, when I was exceptionally lucky, broken English.

The war took me in to the country, and then a few weeks later, it spat me back out. Crossing the border with blisters and saddle sores, I was filthy, with burrs in my socks and rolls of film sewn into my clothes- images that seemed like dreams when I developed them weeks later. How strange to see these black and white blurs take form in a developing bath.

Each time I returned, it seemed that control had changed hands. Mullahs, elders, warlords, bandits and bit players. No wonder the national game is buzkashi, the chaos of horsemen charging around a muddy field for the fleeting triumph of securing the broken carcass of a calf.

Here, I think of the phrase that people murmur constantly, Insha’Allah or God willing, with two upturned palms, as if to catch Allah’s uncertain rain. For Afghans, Allah is the mountain above the mountains, and it is He who entertains the idea- or not- of our next hour on this earth.

This, I think, is why the Afghans are reluctant to bet on tomorrow. Tomorrow is not ours to presume upon.Tomorrow is at the pleasure of Allah alone.

Steve McCurry has been one of the most iconic figures in contemporary photography for more than thirty years. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, McCurry studied cinematography at Pennsylvania State University, before going on to work for a newspaper. After two years, McCurry made his first of what would become many trips to India. Traveling with little more than a bag of clothes and film, he made his way across the subcontinent, exploring the country with his camera.

It was after several months of travel that he crossed the border into Pakistan. In a small village he met a group of refugees from Afghanistan, who smuggled him across the border into their country, just as the Russian invasion was closing the country to Western journalists. Emerging in traditional dress, with full beard and weather-worn features after months embedded with the Mujahideen, McCurry made his way over the Pakistan border with his film sewn into his clothes. McCurry’s images were among the first to show the world the brutality of the Russian invasion.

Since then, McCurry has gone on to create unforgettable images over six continents and numerous countries. His body of work spans conflicts, vanishing cultures, ancient traditions and contemporary culture alike – yet always retains the human element that made his celebrated image of the Afghan Girl such a powerful image. McCurry has been recognized with some of the most prestigious awards including the Robert Capa Gold Medal, National Press Photographers Award, and an unprecedented four first prize awards from the World Press Photo contest amongst dozens of others.

Steve McCurry

In the Shadows of Mountains

McCurry’s Afghanistan may not be the Afghanistan we are expecting. His photographs have the capacity to erode one-dimensional assumptions about the country, allowing the land to be seen in its complexity. We are welcomed into the scene and are surprised by its beauty, even in moments of violence.

McCurry’s intimacy with a place is translated to an intimacy with the people. He is able to capture an intense gaze that draws in the viewer, however, there’s much to gain from the surrounding details as well. He manages a simplicity, or rather, a lack of excess in his composition. And yet, the images are packed with meaningful details, with economy of language. The coal miner’s fingers part for a smoke, yellow fingernails, shirt opened to the air, coal everywhere except the creases on his face. Does he scrunch his forehead the entire time he’s working? Can one smoke in the mine? Presumably not. This moment, heavy with soot, represents relief?

Along with his gifts for atmospheric conveyance, McCurry offers portraiture on a different plane. His images are often minimal but specific, and he only includes the details that matter. The nucleus of each photograph is a point of emotional resonance. It’s no accident that his photographs are seared onto our minds.

Much as outsiders try to reform it, Afghanistan never really changes. It has absorbed blows for millennia, but always continues on as before, defiantly outside of time as we know it. Without even trying, Afghanistan changes everyone who spends time there.

Afghanistan is pastoral and chaotic, peaceful and violent, destroyed and resilient, wonderfully welcoming yet deeply inhospitable.

My Afghan fixation is the story of many journeys. It began in 1979, the year the Russians invaded. Twenty-nine at the time, I had travelled the world, but whatever I had done by that point was no preparation for Afghanistan, especially during a time of war. There was none of the usual military or journalistic structures. There were no seasoned colleagues, armored vehicles or two-way radios.

I slipped across the Pakistan border, following two guides who didn’t speak a word of English. My gear was inadequate; it consisted of a plastic cup, a Swiss Army Knife, two camera bodies, four lenses, a bag of film, a stash of airline peanuts and a soggy copy of Hermann Hesse’s Narcissus and Goldmund that a trekker had left in a $2-a-night hotel.

Over the next weeks, I felt like a lost dog, led by one guide or militia, then another. We moved at night, on foot and on horseback, communicating in sign language and, when I was exceptionally lucky, broken English.

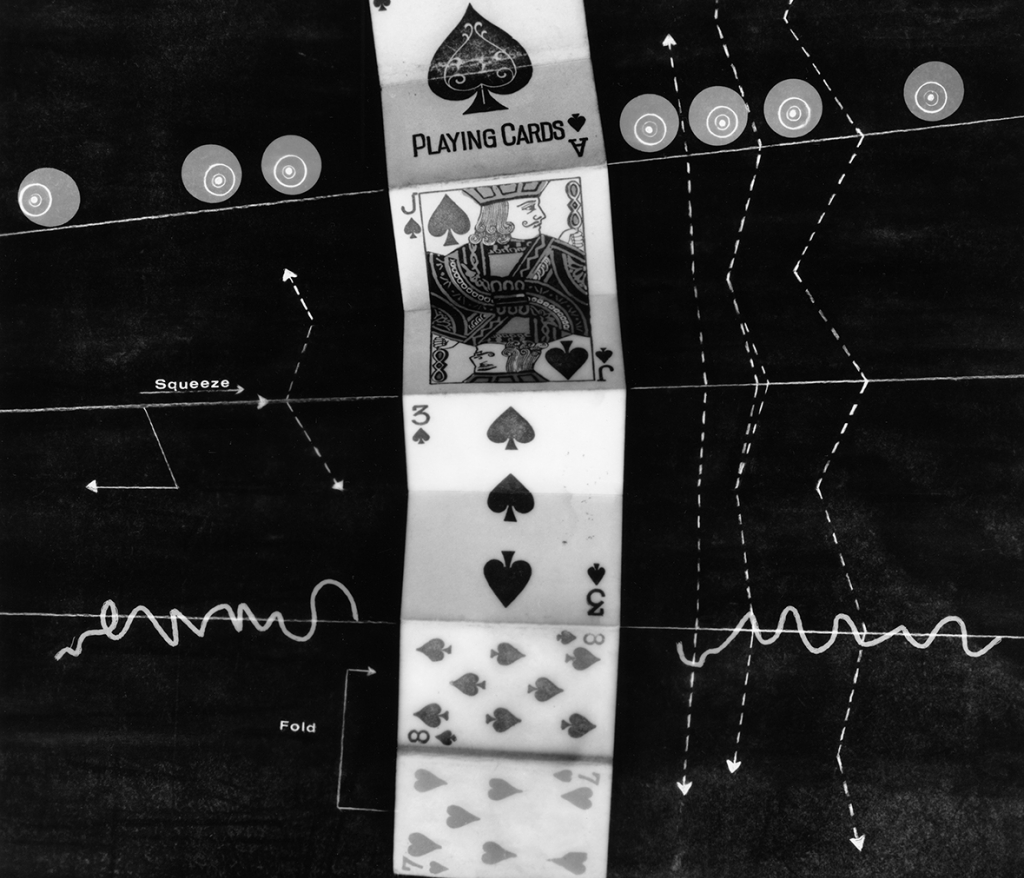

The war took me in to the country, and then a few weeks later, it spat me back out. Crossing the border with blisters and saddle sores, I was filthy, with burrs in my socks and rolls of film sewn into my clothes- images that seemed like dreams when I developed them weeks later. How strange to see these black and white blurs take form in a developing bath.

Each time I returned, it seemed that control had changed hands. Mullahs, elders, warlords, bandits and bit players. No wonder the national game is buzkashi, the chaos of horsemen charging around a muddy field for the fleeting triumph of securing the broken carcass of a calf.

Here, I think of the phrase that people murmur constantly, Insha’Allah or God willing, with two upturned palms, as if to catch Allah’s uncertain rain. For Afghans, Allah is the mountain above the mountains, and it is He who entertains the idea- or not- of our next hour on this earth.

This, I think, is why the Afghans are reluctant to bet on tomorrow. Tomorrow is not ours to presume upon.Tomorrow is at the pleasure of Allah alone.

Steve McCurry has been one of the most iconic figures in contemporary photography for more than thirty years. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, McCurry studied cinematography at Pennsylvania State University, before going on to work for a newspaper. After two years, McCurry made his first of what would become many trips to India. Traveling with little more than a bag of clothes and film, he made his way across the subcontinent, exploring the country with his camera.

It was after several months of travel that he crossed the border into Pakistan. In a small village he met a group of refugees from Afghanistan, who smuggled him across the border into their country, just as the Russian invasion was closing the country to Western journalists. Emerging in traditional dress, with full beard and weather-worn features after months embedded with the Mujahideen, McCurry made his way over the Pakistan border with his film sewn into his clothes. McCurry’s images were among the first to show the world the brutality of the Russian invasion.

Since then, McCurry has gone on to create unforgettable images over six continents and numerous countries. His body of work spans conflicts, vanishing cultures, ancient traditions and contemporary culture alike – yet always retains the human element that made his celebrated image of the Afghan Girl such a powerful image. McCurry has been recognized with some of the most prestigious awards including the Robert Capa Gold Medal, National Press Photographers Award, and an unprecedented four first prize awards from the World Press Photo contest amongst dozens of others.