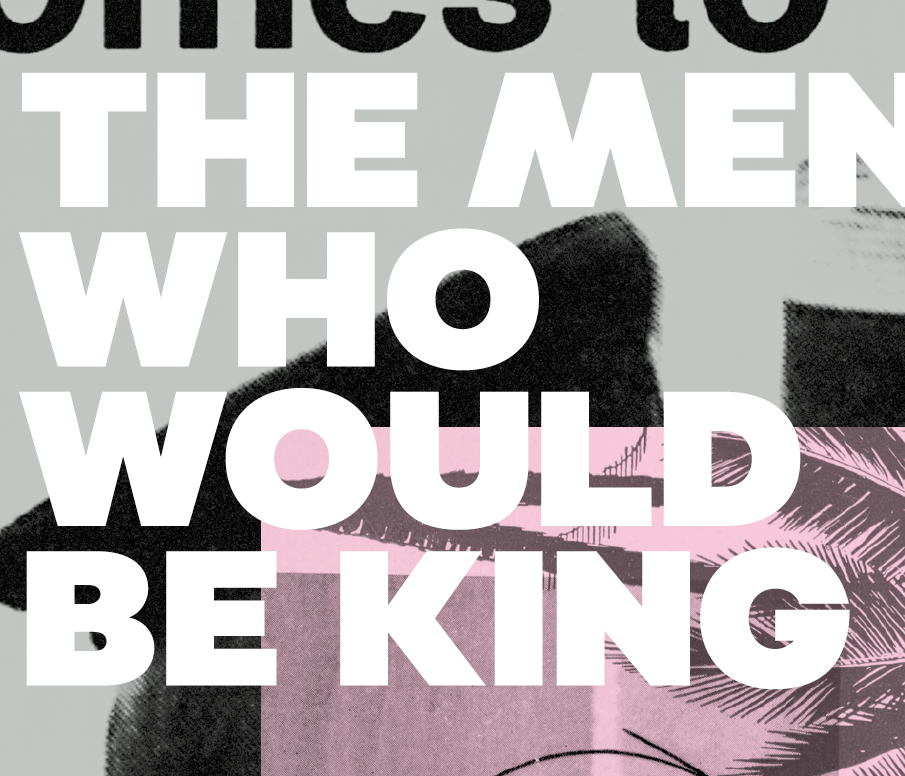

Adam Reynolds

No Lone Zone + Architecture of an Existential Threat

Adam Reynolds

No Lone Zone + Architecture of an Existential Threat

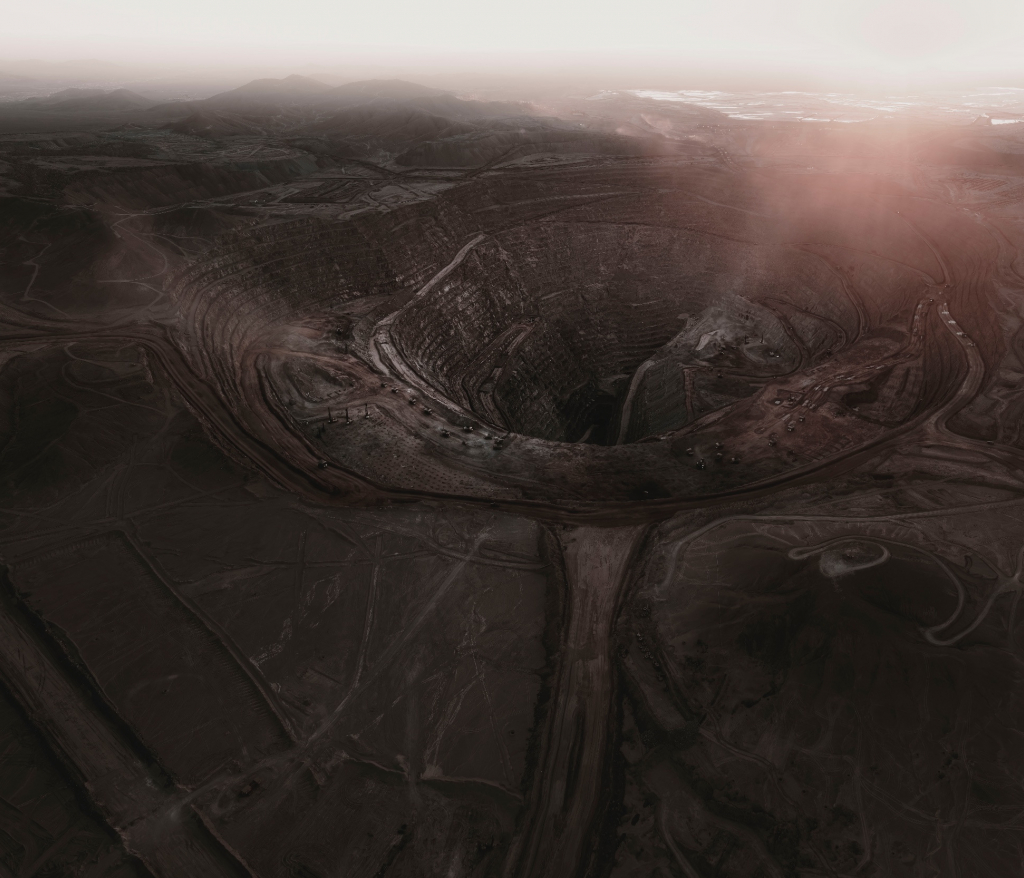

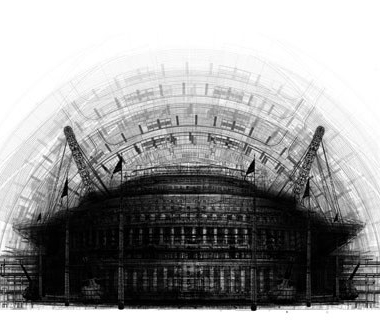

This exhibit brings together two projects examining military might and nuclear power by Adam Reynolds. Although they are made about two entirely distinct conflicts, in different countries and eras, they both bring to light the rooms that have been prepared for the possibility of destruction.

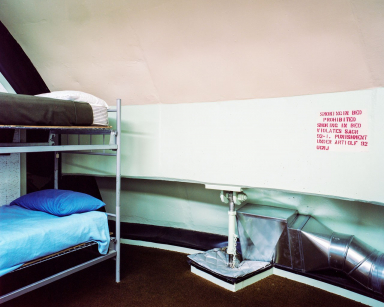

Reynolds offers two vantage points from the game of war, that of military action and civilian response. No Lone Zone explores the vestiges of American nuclear bunkers from the cold war era. From these centers, the government would have launched their offensive in reaction to a perceived threat. Reynolds earlier project, Architecture of an Existential Threat goes down into the bomb shelters of Israel, spaces set aside for citizens to take cover in case of an attack.

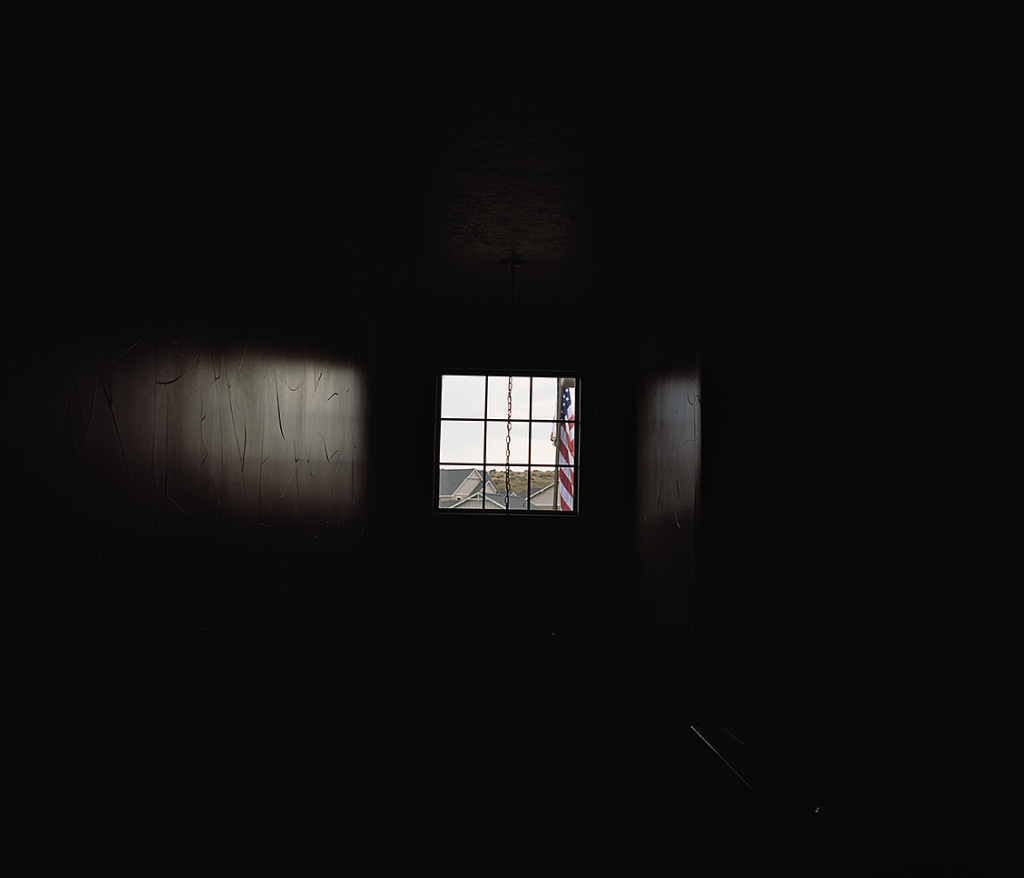

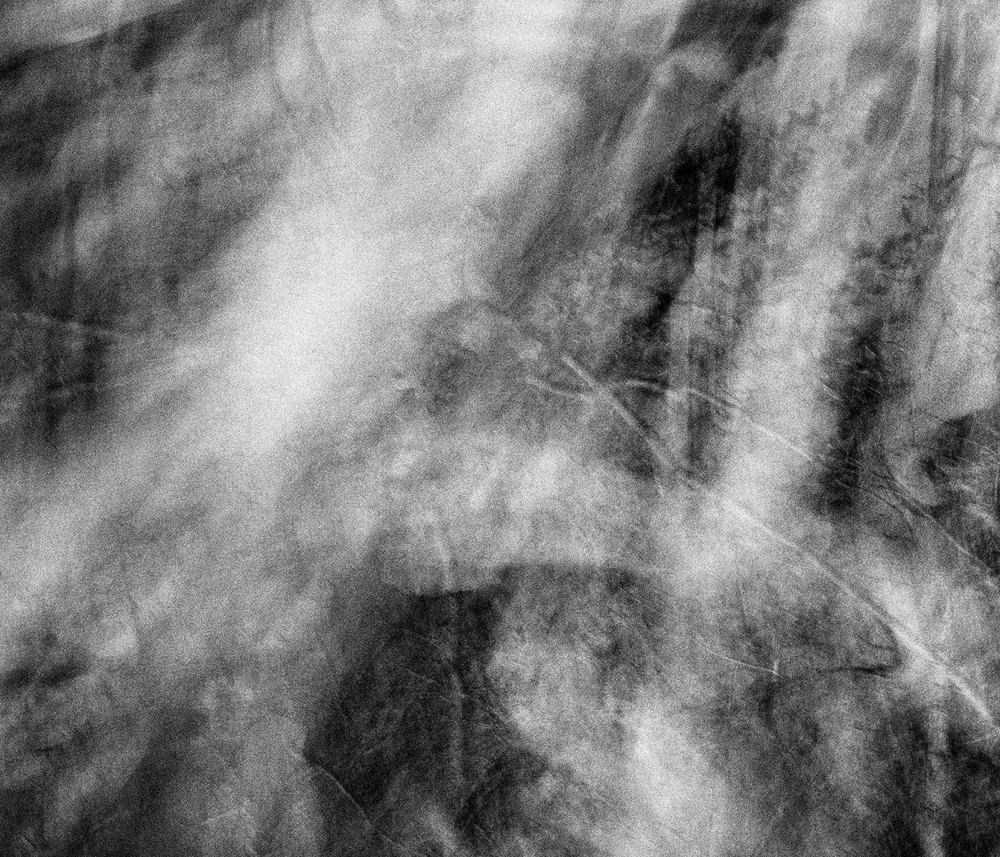

With some of these bomb shelters, Reynolds reveals the volume of the room, and the viewer can briefly inhabit the space while standing in front of the work. With others, he pushes up against the wall, as with the image of a formidable door. This sealed entryway summons a claustrophobic feeling - that there is truly nowhere to go. In the corner of the door frame is a Mizuzah, which is meant to be fixed on the doorpost of every living space in a house of the Jewish religion. This pairing of objects is poignant and dissonant. It suggests that a bomb shelter must also be viewed as a living space.

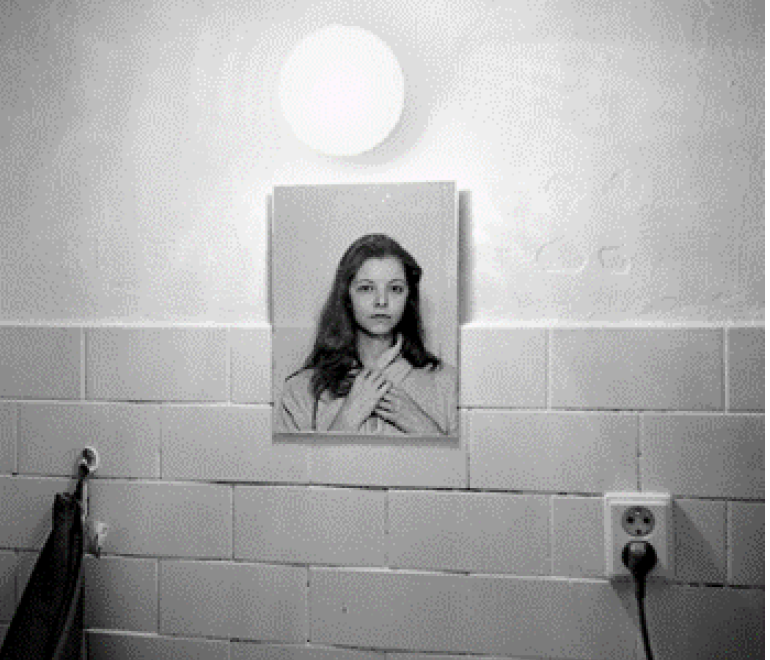

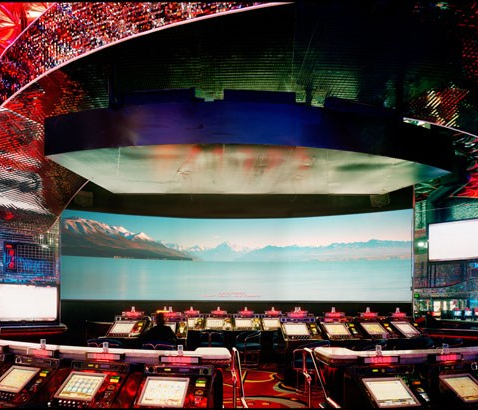

In another photograph, Reynolds frames a couch with a picture of the ocean pasted to the wall above it. For a moment, the ocean is believable, like it’s right there over the wall, and the island in the distance is attainable. A poster of a mirage can become a real mirage in the context of this room, if used to shelter from an attack, when the occupants might find themselves staring at the water on the wall for days.

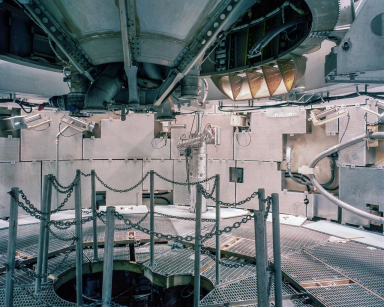

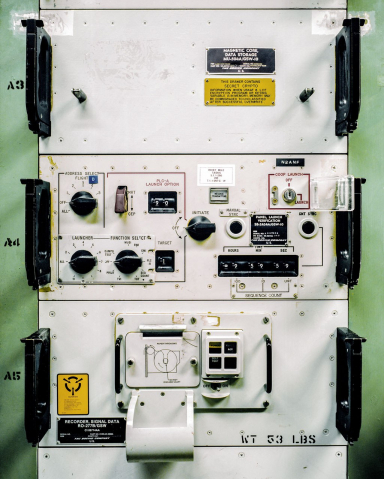

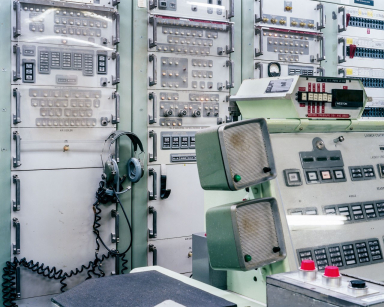

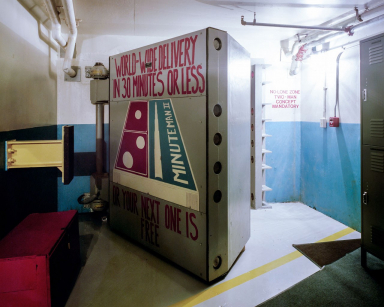

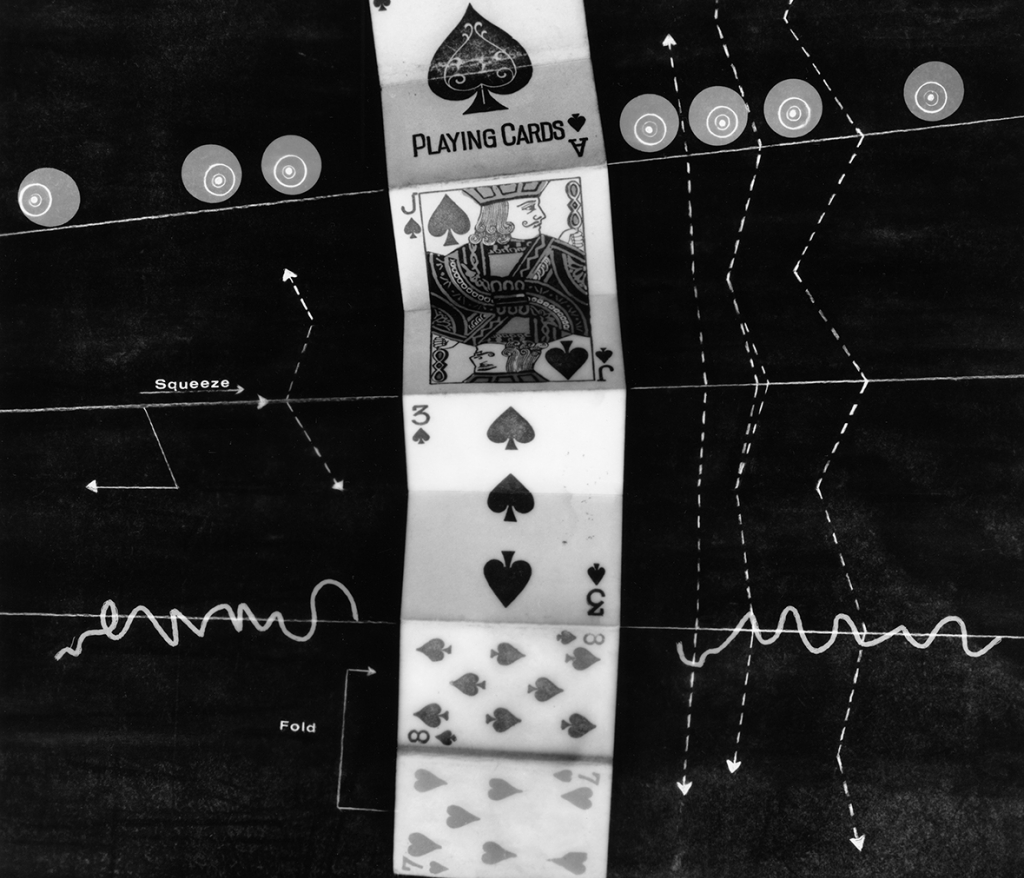

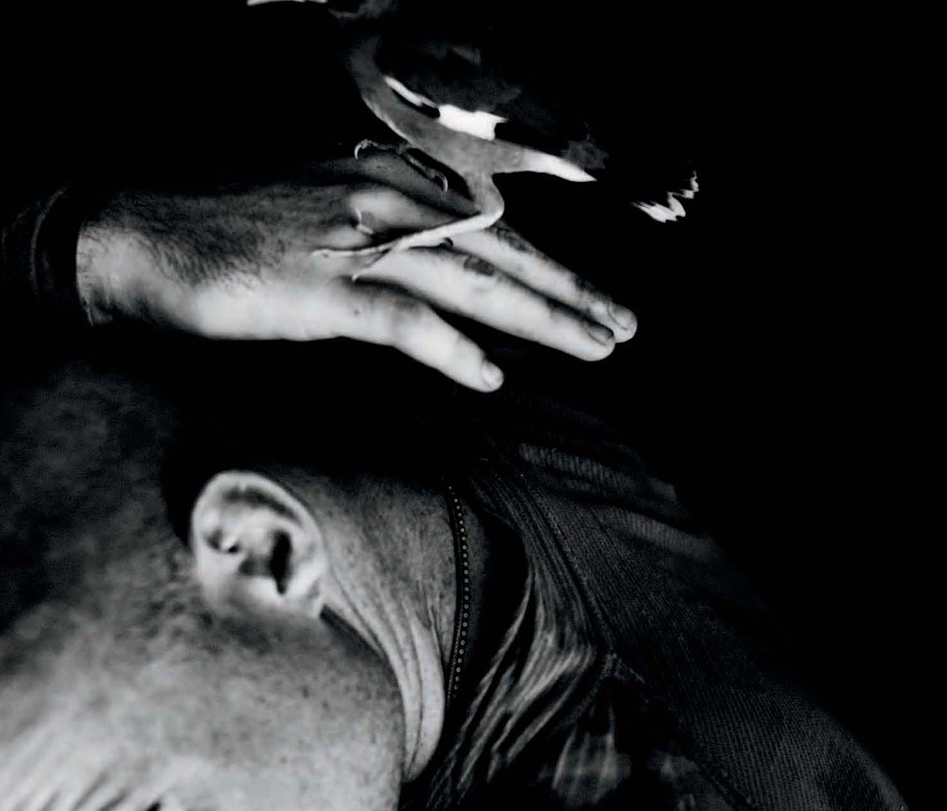

There is an undeniable oddness in bringing pieces of everyday life into a doomsday space, and this tension resonates through both projects. At times, the human traces found in No Lone Zone read like cave paintings that offer small clues about the men who lived there. Reynolds sifts through and exposes artifacts that may feel like symbols to us now. A game of Battleship, a mural of buck hunting, a memorably triumphalist painting of a nuclear missile breaking through a Russian flag; these things become representations of the power that those individuals wielded and lived with.

Everyday life in a place of conflict forms around the real or perceived potential of violence as a daily reality. Although both of Reynold’s projects focus expertly on physical spaces, at their heart, they are about the psychological space of war.

No Lone Zone

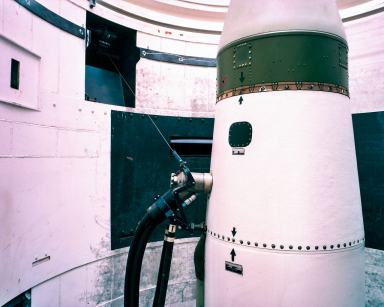

At the height of the Cold War, the United States deployed thousands of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) in a network of underground complexes across the American landscape. These nuclear weapons made up one part of America’s vast deterrent force as it faced off against its ideological rival, the Soviet Union, until its collapse in 1992. And as the Cold War itself has faded from memory, so too have the lessons and fears these weapons once elicited in the general public. Yet the issue of unchecked nuclear proliferation has returned that fear to the forefront.

With much of America’s Cold War era nuclear arsenal deactivated and dismantled today, there are a growing number of former missile sites whose mission is to preserve the history and memory of the period. These frozen time capsules are open to the public, catering to an array of nostalgic “nuclear tourists.” As “Shrines to an Armageddon,” they preserve the dramatic vestiges of a power that can destroy the world. The sites stand sentinel as potent reminders of American military might, but also serve as a cautionary tale for future generations.

Two such sites, the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota and the Titan Missile Museum in Arizona, are the only remaining ICBM sites in the United States that not only allow visitors into the underground launch control center, but also to come face to face with a (nonfunctioning) intercontinental ballistic missile as well.

The project’s title refers to the Air Force’s mandatory two-person buddy system in place at all ICBM sites. This applied both to the on-duty officers on 24-hour alert in the launch control center and to the work crews tasked with maintaining the missiles. The policy was intended as a safety precaution and as a safeguard against potential sabotage. The images pair America’s most prolific ICBM (the Minuteman II) with its most powerful (the Titan II) and offer a calculated look at the nuts and bolts of Mutually Assured Destruction, the mad logic behind nuclear deterrence.

Architecture of an Existential Threat

Since its creation in 1948, the State of Israel has felt itself isolated and beset by enemies seeking its destruction. This collective siege mentality is best expressed in the ubiquity of the thousands of bomb shelters found throughout the country. By law all Israelis are required to have access to a bomb shelter and rooms that can be sealed off in case of an unconventional weapons attack. There are over one million public and private bomb shelters found throughout Israel and the Occupied Territories.

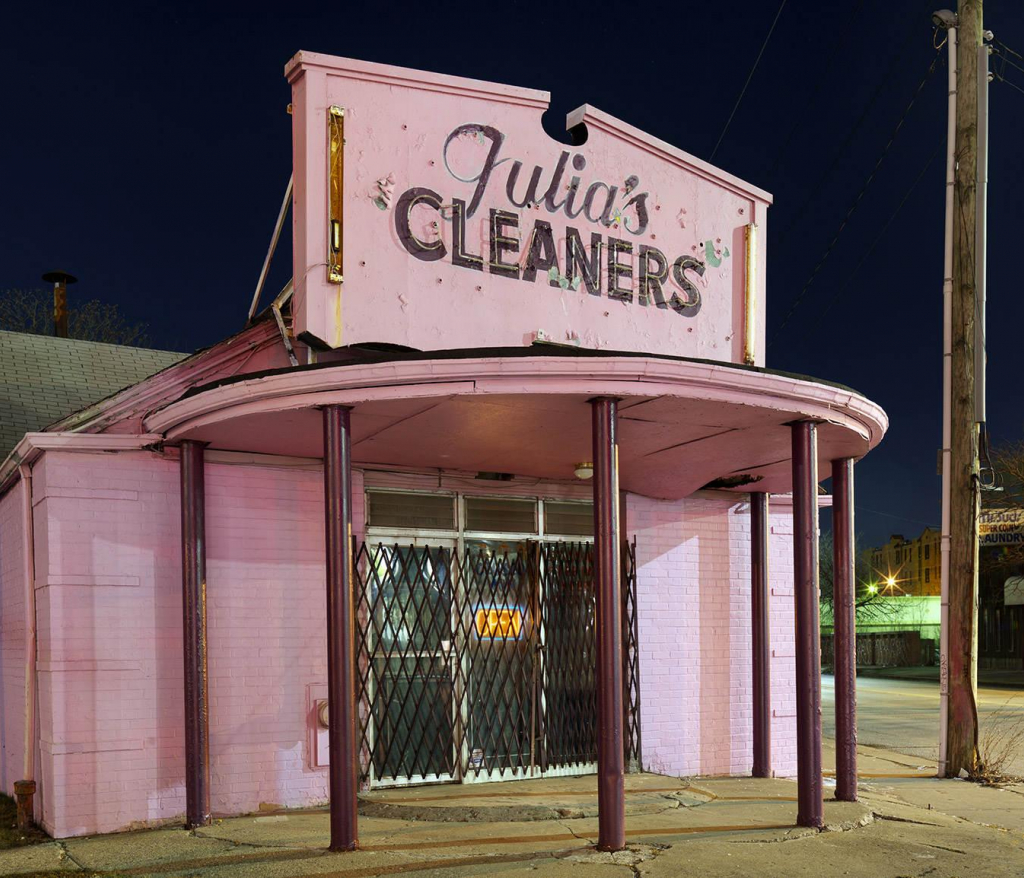

The photographs in this series document these bomb shelters and offer a window into the collective mindset of the Israeli people. Israelis have normalized this “doomsday space” into their daily lives, often using the shelters as dance studios, community centers, pubs, and places of worship. For Jewish Israelis haunted by a history of exile and persecution, these shelters are the architecture of an existential threat – both real and perceived.

Adam Reynolds is a documentary photographer whose work focuses on contemporary political conflict, with a particular emphasis on the Middle East. He pursues research projects that balance photographic creativity with a journalist’s thematic fidelity. He holds a Masters of Fine Art degree in photography from Indiana University. He began his career covering the Middle East in 2007 as a freelance photojournalist. Adam holds undergraduate degrees in journalism and political science from Indiana University with a focus in photojournalism and Middle Eastern politics. He also holds a Masters degree in Islamic and Middle East Studies from Hebrew University in Jerusalem.

Adam Reynolds

No Lone Zone + Architecture of an Existential Threat

This exhibit brings together two projects examining military might and nuclear power by Adam Reynolds. Although they are made about two entirely distinct conflicts, in different countries and eras, they both bring to light the rooms that have been prepared for the possibility of destruction.

Reynolds offers two vantage points from the game of war, that of military action and civilian response. No Lone Zone explores the vestiges of American nuclear bunkers from the cold war era. From these centers, the government would have launched their offensive in reaction to a perceived threat. Reynolds earlier project, Architecture of an Existential Threat goes down into the bomb shelters of Israel, spaces set aside for citizens to take cover in case of an attack.

With some of these bomb shelters, Reynolds reveals the volume of the room, and the viewer can briefly inhabit the space while standing in front of the work. With others, he pushes up against the wall, as with the image of a formidable door. This sealed entryway summons a claustrophobic feeling - that there is truly nowhere to go. In the corner of the door frame is a Mizuzah, which is meant to be fixed on the doorpost of every living space in a house of the Jewish religion. This pairing of objects is poignant and dissonant. It suggests that a bomb shelter must also be viewed as a living space.

In another photograph, Reynolds frames a couch with a picture of the ocean pasted to the wall above it. For a moment, the ocean is believable, like it’s right there over the wall, and the island in the distance is attainable. A poster of a mirage can become a real mirage in the context of this room, if used to shelter from an attack, when the occupants might find themselves staring at the water on the wall for days.

There is an undeniable oddness in bringing pieces of everyday life into a doomsday space, and this tension resonates through both projects. At times, the human traces found in No Lone Zone read like cave paintings that offer small clues about the men who lived there. Reynolds sifts through and exposes artifacts that may feel like symbols to us now. A game of Battleship, a mural of buck hunting, a memorably triumphalist painting of a nuclear missile breaking through a Russian flag; these things become representations of the power that those individuals wielded and lived with.

Everyday life in a place of conflict forms around the real or perceived potential of violence as a daily reality. Although both of Reynold’s projects focus expertly on physical spaces, at their heart, they are about the psychological space of war.

No Lone Zone

At the height of the Cold War, the United States deployed thousands of Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM) in a network of underground complexes across the American landscape. These nuclear weapons made up one part of America’s vast deterrent force as it faced off against its ideological rival, the Soviet Union, until its collapse in 1992. And as the Cold War itself has faded from memory, so too have the lessons and fears these weapons once elicited in the general public. Yet the issue of unchecked nuclear proliferation has returned that fear to the forefront.

With much of America’s Cold War era nuclear arsenal deactivated and dismantled today, there are a growing number of former missile sites whose mission is to preserve the history and memory of the period. These frozen time capsules are open to the public, catering to an array of nostalgic “nuclear tourists.” As “Shrines to an Armageddon,” they preserve the dramatic vestiges of a power that can destroy the world. The sites stand sentinel as potent reminders of American military might, but also serve as a cautionary tale for future generations.

Two such sites, the Minuteman Missile National Historic Site in South Dakota and the Titan Missile Museum in Arizona, are the only remaining ICBM sites in the United States that not only allow visitors into the underground launch control center, but also to come face to face with a (nonfunctioning) intercontinental ballistic missile as well.

The project’s title refers to the Air Force’s mandatory two-person buddy system in place at all ICBM sites. This applied both to the on-duty officers on 24-hour alert in the launch control center and to the work crews tasked with maintaining the missiles. The policy was intended as a safety precaution and as a safeguard against potential sabotage. The images pair America’s most prolific ICBM (the Minuteman II) with its most powerful (the Titan II) and offer a calculated look at the nuts and bolts of Mutually Assured Destruction, the mad logic behind nuclear deterrence.

Architecture of an Existential Threat

Since its creation in 1948, the State of Israel has felt itself isolated and beset by enemies seeking its destruction. This collective siege mentality is best expressed in the ubiquity of the thousands of bomb shelters found throughout the country. By law all Israelis are required to have access to a bomb shelter and rooms that can be sealed off in case of an unconventional weapons attack. There are over one million public and private bomb shelters found throughout Israel and the Occupied Territories.

The photographs in this series document these bomb shelters and offer a window into the collective mindset of the Israeli people. Israelis have normalized this “doomsday space” into their daily lives, often using the shelters as dance studios, community centers, pubs, and places of worship. For Jewish Israelis haunted by a history of exile and persecution, these shelters are the architecture of an existential threat – both real and perceived.

Adam Reynolds is a documentary photographer whose work focuses on contemporary political conflict, with a particular emphasis on the Middle East. He pursues research projects that balance photographic creativity with a journalist’s thematic fidelity. He holds a Masters of Fine Art degree in photography from Indiana University. He began his career covering the Middle East in 2007 as a freelance photojournalist. Adam holds undergraduate degrees in journalism and political science from Indiana University with a focus in photojournalism and Middle Eastern politics. He also holds a Masters degree in Islamic and Middle East Studies from Hebrew University in Jerusalem.