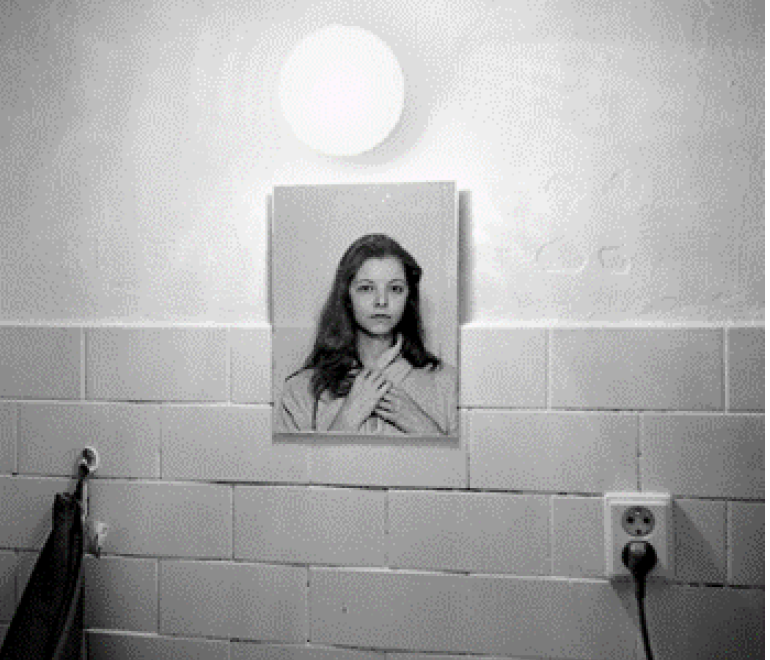

Antonio Bolfo

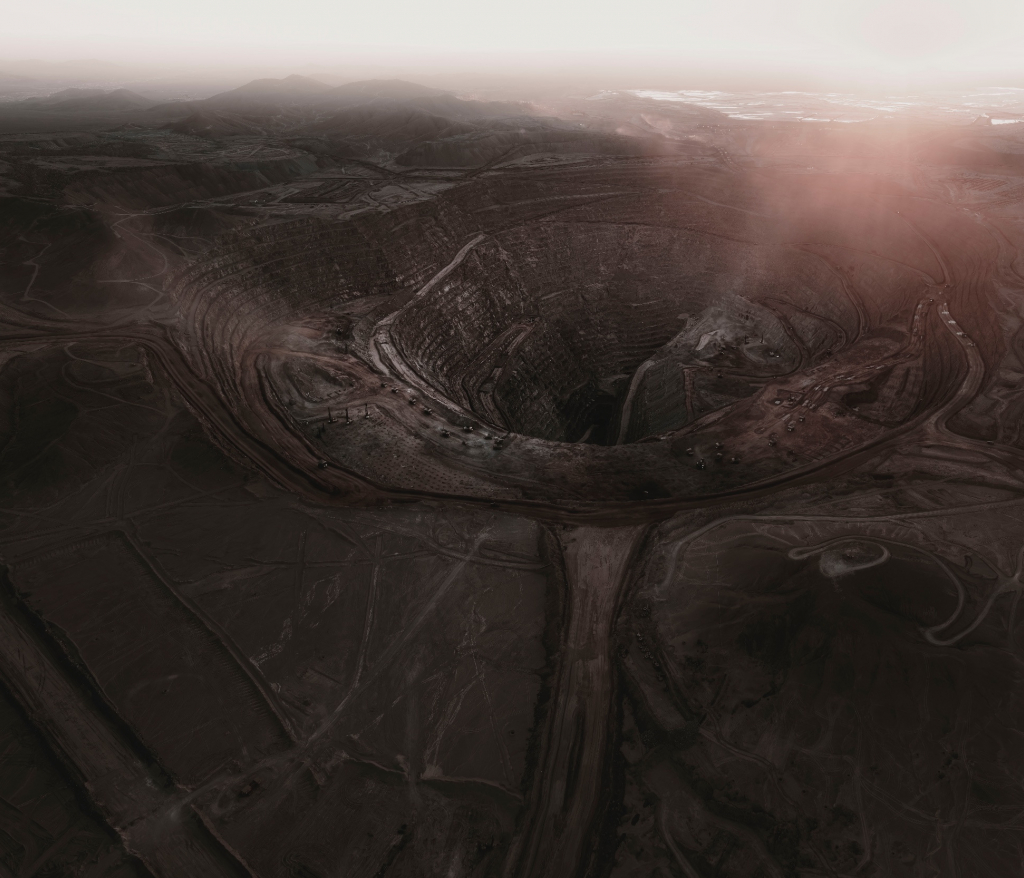

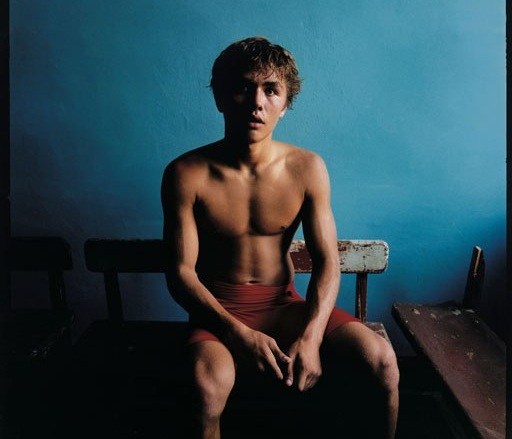

Cite Soleil, Haiti

Antonio Bolfo

Cite Soleil, Haiti

Antonio Bolfo was born and raised in New York City. He attended the Rhode Island School of Design, earning a BFA in film, animation and video. He then became the senior animator at the video game development company Harmonix. For four years he worked on Playstation games such as Guitar Hero, Amplitude, and Anti-Grav, among others.

Antonio left the video game industry to become an NYPD police officer and was assigned to the South Bronx housing projects. It was here that he found his love for photography, which propelled him to attend the International Center of Photography to study photojournalism.

He is the recipient of The New York Times Foundation Scholarship, 1st place winner in the 2011 National Press Photographers Association’s Best of Photojournalism, winner in the 2009 World Wide Photography Gala Awards, and a 2011 participant in the World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass. His work has been published in The New York Times, Time Magazine, Newsweek, and American Photography, among others.

He is based in New York City and is a core member of Reportage by Getty Images.

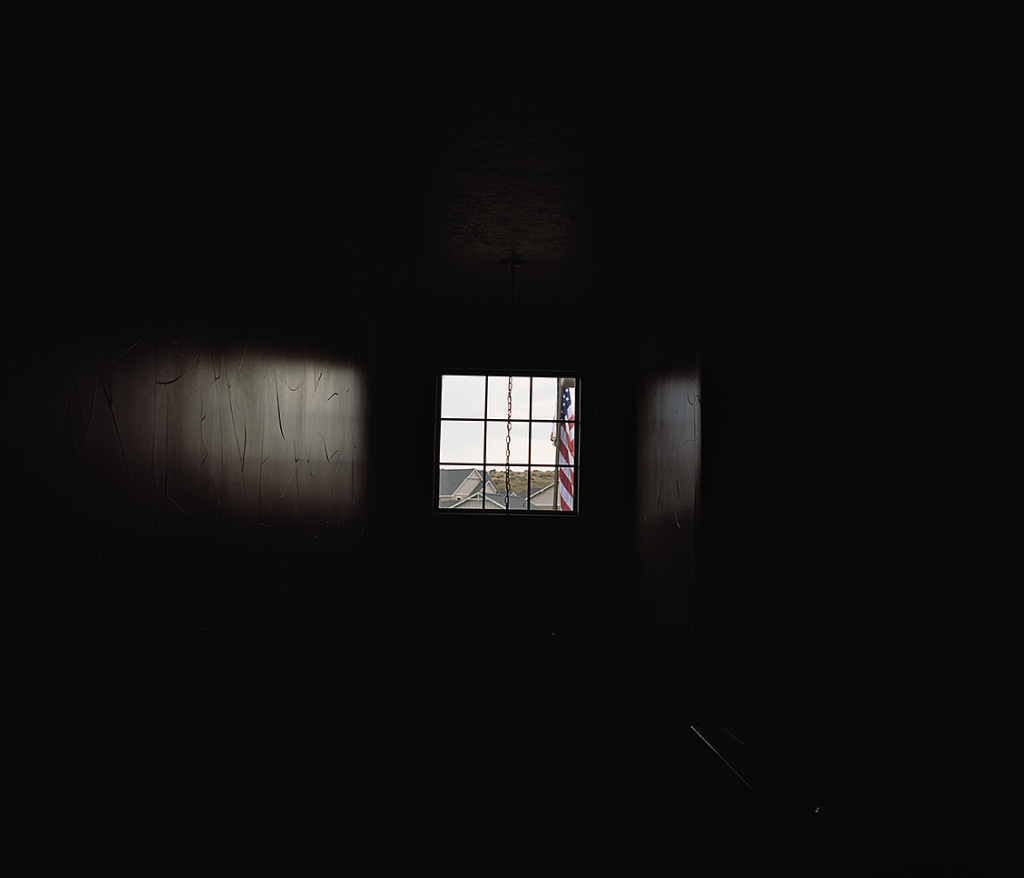

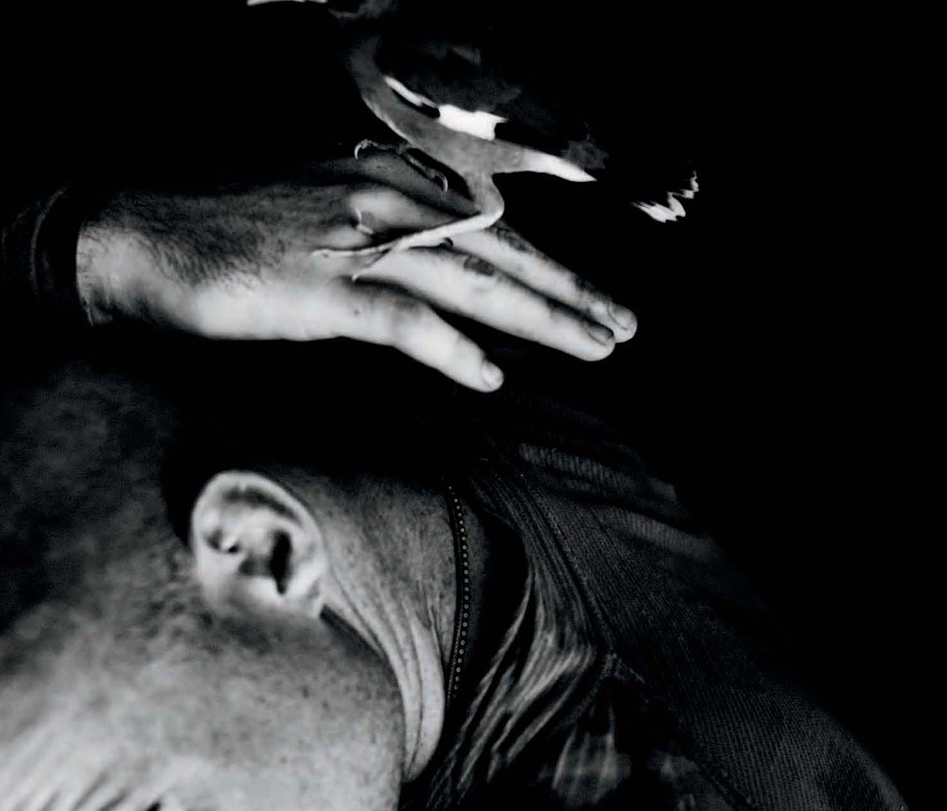

I have been working on this photo project since the autumn of 2008. It has been a personal journey and a means of closure for a period of my life. This story of rookie cops is one that I lived myself, and it is something I feel needs to be told. I hope this project will offer a glimpse into the reality that is often veiled behind the curtain of TV shows and action films. It was not the politics, or the social statements, or the action that attracted me to this project, but the story of the people who learn to be police officers through a trial by fire.

I was a police officer from 2006 to 2008 in the NYPD. Four days after graduating from Police Academy I was ordered to PSA 7, a housing precinct in the South Bronx that patrols some of America’s most crime- ridden housing projects. American popular culture has demonized the housing projects as a haven for drug dealers, gangs, addicts, and murderers. But they are also people’s homes, the most intimate environment of a person’s life.

As part of the standard operating procedure, I was assigned to Operation Impact, a unit that consists only of rookies. Prior to this, I had six months of Police Academy classroom training, along with some gym sessions where they made us run in circles with five-minute intervals of punching and kicking. Our firearms training consisted of one week of shooting at immobile targets at the NYPD shooting range. We were as green as could be, and like other Impact officers, I hit the ground running with little to no knowledge of how to operate on the street. Yet we were expected to apprehend some of the toughest and most intelligent people in the city.

We were expected to solve family disputes, console the parents of murdered children, and entertain the neighborhood drunk. The majority of what we encountered was negative, since no one calls the police when they’re happy. We had no choice but to learn fast, but learning comes from making mistakes, and unfortunately we all made a lot of them. Despite some of the shortcomings, I loved police work and instantly felt camaraderie, excitement, and sense of adventure. But more than anything, I learned about myself and about humanity in ways that I never thought possible.

I think many people who choose to become police officers do so with some optimism and hope that they can make a difference. But unfortunately, in a community like South Bronx Housing, the reality comes crashing down on you very fast. It only takes a few weeks for any romanticized view of community policing to get thrown out the window and be replaced by a fortifying mentality of hostility and resentment that many officers in the ghetto feel.

As a brand new officer everything was new and exciting to me: from the human excrement that littered the walls of the stairwells to violent apprehensions with no backup on the top floors of the projects. But it grows old fast, and the euphoria and adrenaline that come from solving family drama and hunting people wanes. I soon became aware of the emotional stress that my experiences were having on me, and realized that the impact of The Job was affecting my everyday life. Some cops have stronger emotional shields than others, but sooner or later I think it affects everybody. There was a substantial amount of depression in the unit and at the precinct in general, but no one would ever admit it out of fear it would be taken as a sign of weakness. People deal with depression in a number of ways, some take to alcohol, others to infidelity. For me it was photography that helped ease the burden. Although I loved police work, I soon found myself wanting to take photographs of police work more than doing the work itself. It started to feel more important and useful, and it was a fusion of everything that I had come to love. We all joined the NYPD in search of something, and I found it in the hallways, stairs, and apartments of the housing projects.

-Antonio Bolfo

Antonio Bolfo

Cite Soleil, Haiti

Antonio Bolfo was born and raised in New York City. He attended the Rhode Island School of Design, earning a BFA in film, animation and video. He then became the senior animator at the video game development company Harmonix. For four years he worked on Playstation games such as Guitar Hero, Amplitude, and Anti-Grav, among others.

Antonio left the video game industry to become an NYPD police officer and was assigned to the South Bronx housing projects. It was here that he found his love for photography, which propelled him to attend the International Center of Photography to study photojournalism.

He is the recipient of The New York Times Foundation Scholarship, 1st place winner in the 2011 National Press Photographers Association’s Best of Photojournalism, winner in the 2009 World Wide Photography Gala Awards, and a 2011 participant in the World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass. His work has been published in The New York Times, Time Magazine, Newsweek, and American Photography, among others.

He is based in New York City and is a core member of Reportage by Getty Images.

I have been working on this photo project since the autumn of 2008. It has been a personal journey and a means of closure for a period of my life. This story of rookie cops is one that I lived myself, and it is something I feel needs to be told. I hope this project will offer a glimpse into the reality that is often veiled behind the curtain of TV shows and action films. It was not the politics, or the social statements, or the action that attracted me to this project, but the story of the people who learn to be police officers through a trial by fire.

I was a police officer from 2006 to 2008 in the NYPD. Four days after graduating from Police Academy I was ordered to PSA 7, a housing precinct in the South Bronx that patrols some of America’s most crime- ridden housing projects. American popular culture has demonized the housing projects as a haven for drug dealers, gangs, addicts, and murderers. But they are also people’s homes, the most intimate environment of a person’s life.

As part of the standard operating procedure, I was assigned to Operation Impact, a unit that consists only of rookies. Prior to this, I had six months of Police Academy classroom training, along with some gym sessions where they made us run in circles with five-minute intervals of punching and kicking. Our firearms training consisted of one week of shooting at immobile targets at the NYPD shooting range. We were as green as could be, and like other Impact officers, I hit the ground running with little to no knowledge of how to operate on the street. Yet we were expected to apprehend some of the toughest and most intelligent people in the city.

We were expected to solve family disputes, console the parents of murdered children, and entertain the neighborhood drunk. The majority of what we encountered was negative, since no one calls the police when they’re happy. We had no choice but to learn fast, but learning comes from making mistakes, and unfortunately we all made a lot of them. Despite some of the shortcomings, I loved police work and instantly felt camaraderie, excitement, and sense of adventure. But more than anything, I learned about myself and about humanity in ways that I never thought possible.

I think many people who choose to become police officers do so with some optimism and hope that they can make a difference. But unfortunately, in a community like South Bronx Housing, the reality comes crashing down on you very fast. It only takes a few weeks for any romanticized view of community policing to get thrown out the window and be replaced by a fortifying mentality of hostility and resentment that many officers in the ghetto feel.

As a brand new officer everything was new and exciting to me: from the human excrement that littered the walls of the stairwells to violent apprehensions with no backup on the top floors of the projects. But it grows old fast, and the euphoria and adrenaline that come from solving family drama and hunting people wanes. I soon became aware of the emotional stress that my experiences were having on me, and realized that the impact of The Job was affecting my everyday life. Some cops have stronger emotional shields than others, but sooner or later I think it affects everybody. There was a substantial amount of depression in the unit and at the precinct in general, but no one would ever admit it out of fear it would be taken as a sign of weakness. People deal with depression in a number of ways, some take to alcohol, others to infidelity. For me it was photography that helped ease the burden. Although I loved police work, I soon found myself wanting to take photographs of police work more than doing the work itself. It started to feel more important and useful, and it was a fusion of everything that I had come to love. We all joined the NYPD in search of something, and I found it in the hallways, stairs, and apartments of the housing projects.

-Antonio Bolfo