Kurt Tong + Patrick Wack

Kurt Tong + Patrick Wack

In their respective projects, roaming particular regions within China, both Patrick Wack and Kurt Tong work through the complicated facets of their own capacity to romanticize the land. The photographic stories they produce benefit from their introspective efforts. Both artists display candor as they grapple with the responsibility of representing a particular place, even as they struggle to know and understand the regions that have called to their imaginations.

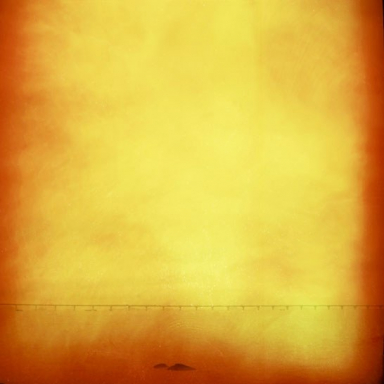

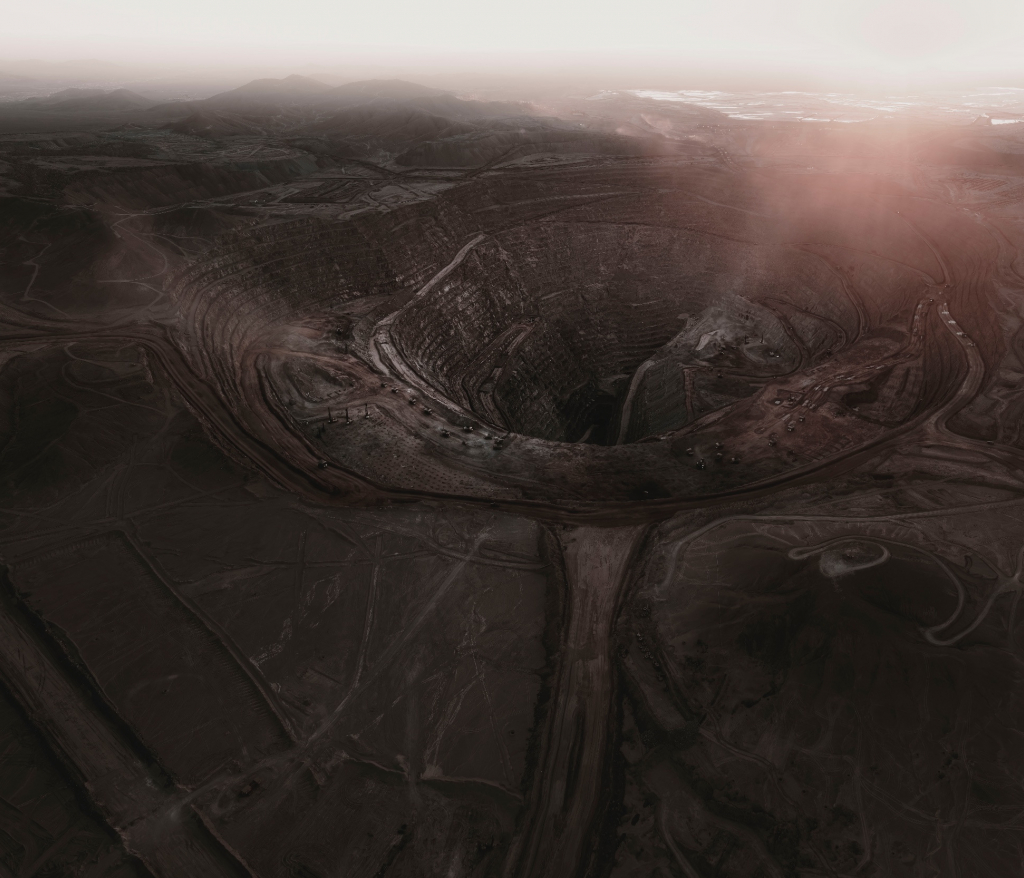

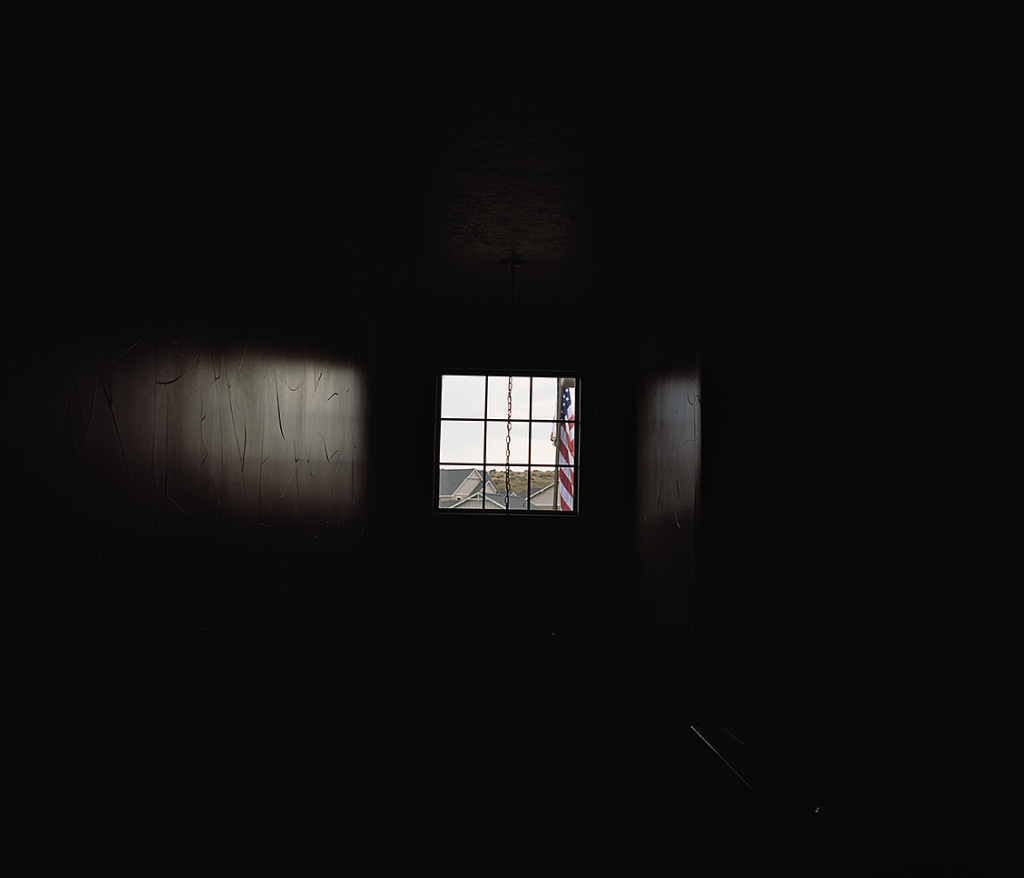

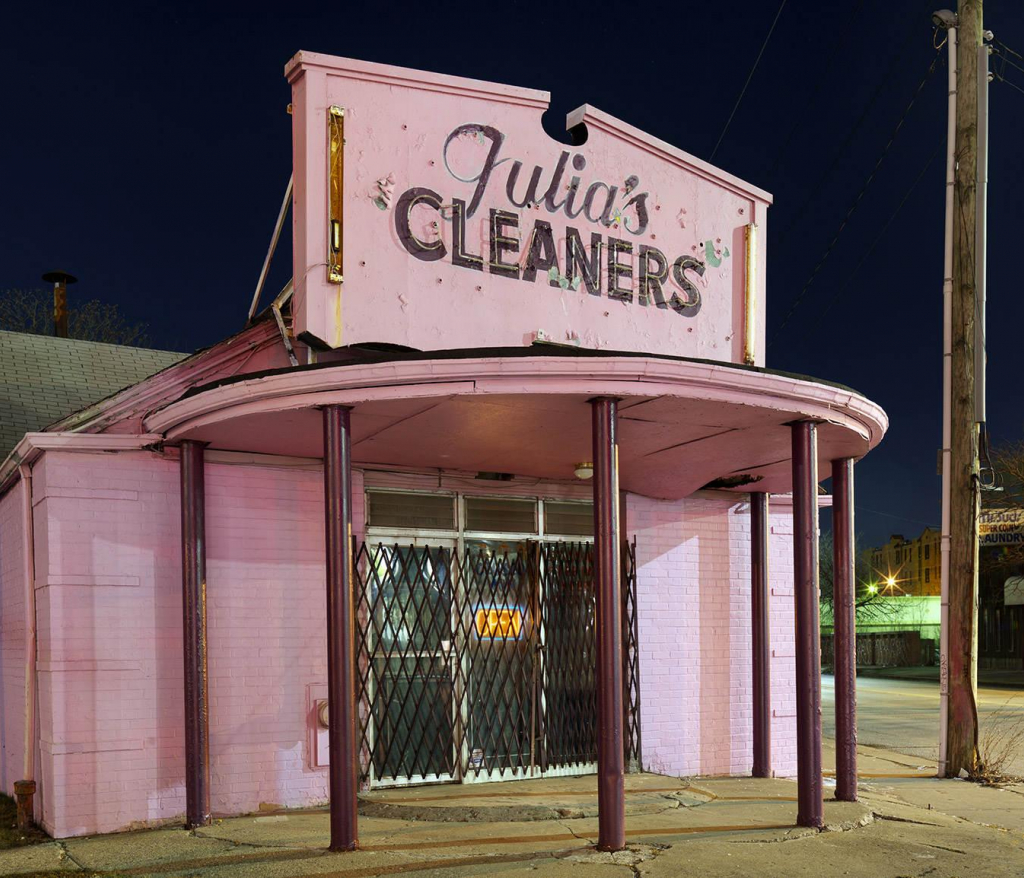

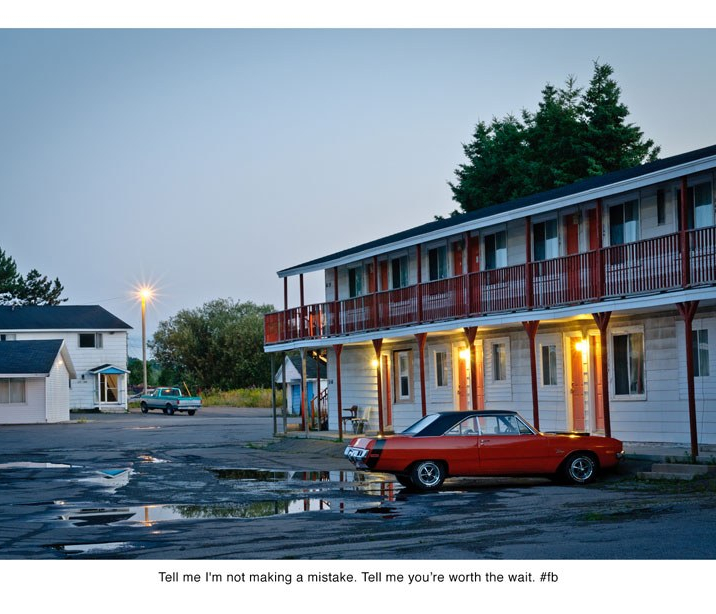

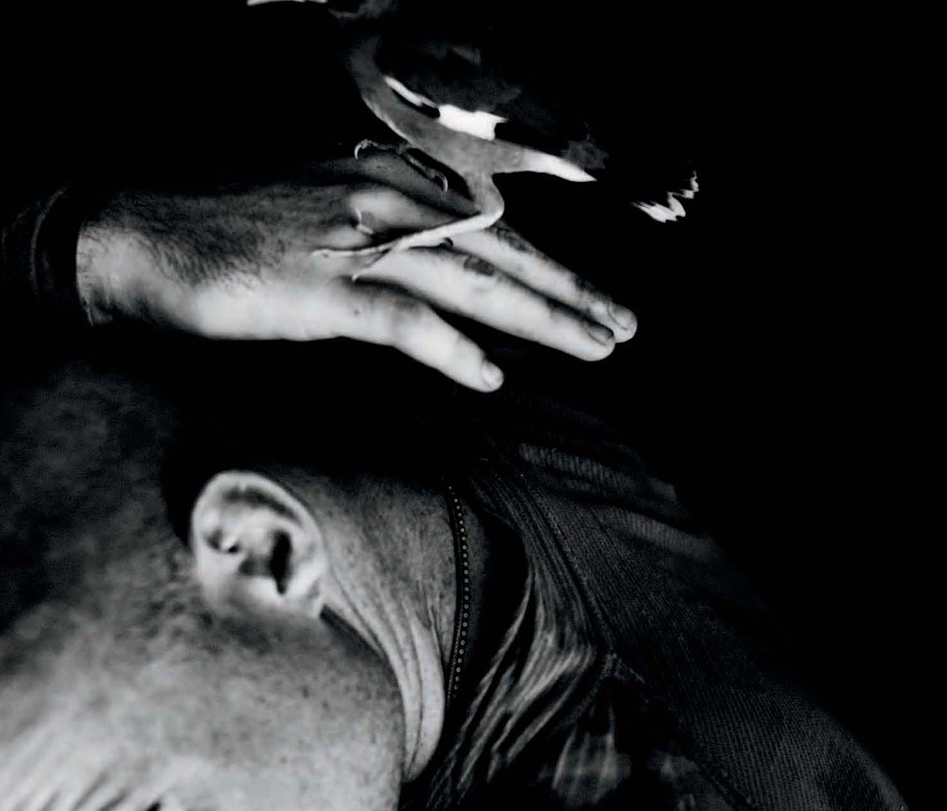

For Tong, the call came from the desire to connect with his motherland. For Wack, the call came from the modern day frontier. Anticipating the adventure of the outer limits, Wack set out to explore Xinjiang, China’s westernmost region. He deftly documented the many faces of the natural and cultural landscapes of the region. Wack’s image of an old armchair and makeshift table, abandoned in front of a majestic wilderness, seems to be channelling Richard Misrach’s work without even knowing it. His palette of sand and oil conjure the aesthetics of the American western tradition. Wack uses the act of the photographic search as a metaphor for himself as well. He describes the process as an emotional journey “of what it means to strive, and for what.”

Both projects search for cultural identity, and they both acknowledge an inability to create a clean and tidy box from what they’ve found. Looking to his ancestral roots, Kurt Tong returned to his motherland to the cities of Zhongshan and Guangzhou, where his ancestors lived and worked. He came to the project, his mind pre-loaded with nostalgic images, in search of connection and a place of belonging.

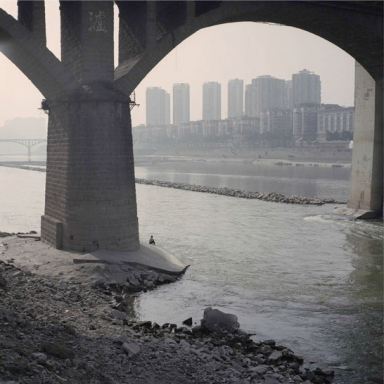

In ‘Chongqing III’, at the left side of the frame, a solitary man walks down a bit of dirt road with hands folded behind his back, and a highway overhead. To his right, there is a fragment of what we imagine to be the old, traditional city. Although now dilapidated, it carries echoes of a poetic and pastoral past. In front of the man spreads a horizon of modern city buildings, which look equally worn. To which world does the man belong? His presence on the road that straddles these two spheres is a question mark, as Tong does not reveal where he is coming from or where he is going. Perhaps this man’s life, like Tong’s, exists not in one place or the other, but somewhere in between the two.

Photography is captivating in the sense of reality that it conveys. A picture so instantly places the viewer in the world of the photograph, often without much awareness that the artist’s hand is shaping and filtering what is seen. When we first saw these bodies of work, we knew that they were perfect for Pictura’s inaugural opening at its new home in the FAR Center for Contemporary Arts. Both projects transport the viewer and communicate aesthetically and emotionally about the places they depict. They exemplify qualities that makes the photographic medium so particularly powerful, a rich combination of immediacy, subtle narrative, and beauty.

Born in Hong Kong in 1977, Kurt Tong became a full-time photographer in 2003. He was the winner of the Luis Valtuena International Humanitarian Photography Award and has worked for a number of other NGOs. He gained his Masters in documentary photography at the LCC in 2006 and began working on more personal projects exploring his Chinese roots and understanding of his motherland. A monograph of ‘In Case it Rains in Heaven’ exploring the practice of Chinese funeral offerings, was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2011.Tong’s project ‘The Queen, The Chairman and I’ has been exhibited across 4 continents, including the Victoria Museum in Liverpool, UK; Galleri Image in Denmark; the Visual Art Center at the Chinese Cultural Foundation of San Francisco, Impressions Gallery in Bradford and will be traveling to Lianzhou Photography Museum in 2018.‘Combing for Ice and Jade’, a love letter to the artist’s nanny, one of the few remaining self combed women (Chinese women who pledged never to marry) in the world, has won him the WMA and the Punctum award at Lianzhou Foto. The installation was recently shown at the Himalayas Museum in Shanghai and will be travelling to the Zhongshan Museum of Art in 2018. He is represented by Jen Bekman Gallery in New York, The Photographer’s Gallery in London.

Sweet Water, Bitter Earth | Artist Statement

Chinese in Hong Kong, in Taiwan, and overseas often struggle with their Chinese identity, many have an idealized image of what the motherland is like, whether it’s from stories retold by our relatives, from a romanticized view of a movie. The reality is often very different, especially given the accelerated speed at which China is changing. It is often this failure to meet our expectations and the vast, often unexpected difference in cultures that alienate us from feeling comfortable and secure with our roots.

My paternal ancestral line has strong affiliation with the sea, as fisherman, as deckhands, as traders, marine tragedies also wiped out entire arms of the family. My maternal ancestral line on the other hand, has strong affiliation with the land, as landlords, as builders.

However, while trying to photograph these two cities, I realized how little connection I have with either of these places, emotionally or physically. I realized that my own vision of china was also shaped by TV shows of my childhood and more recently, photographic projects made in China.

I went further into China in search of my own preconceived images of China.

I traveled to all corners of the vast country, trying to find my own connection with my supposed motherland. I found a strange sense of belonging and emotional tide to the landscapes, however, as I got closer to the people, I felt disconnected and alienated. I realized that it is modern day China and its people that I don’t understand and my dream of redemption and return to a lost homeland is ultimately, a failure.

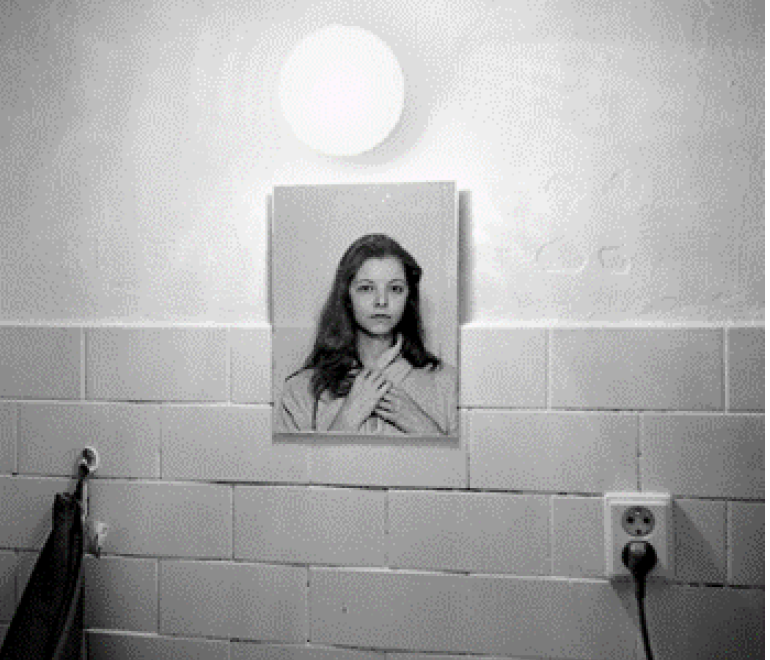

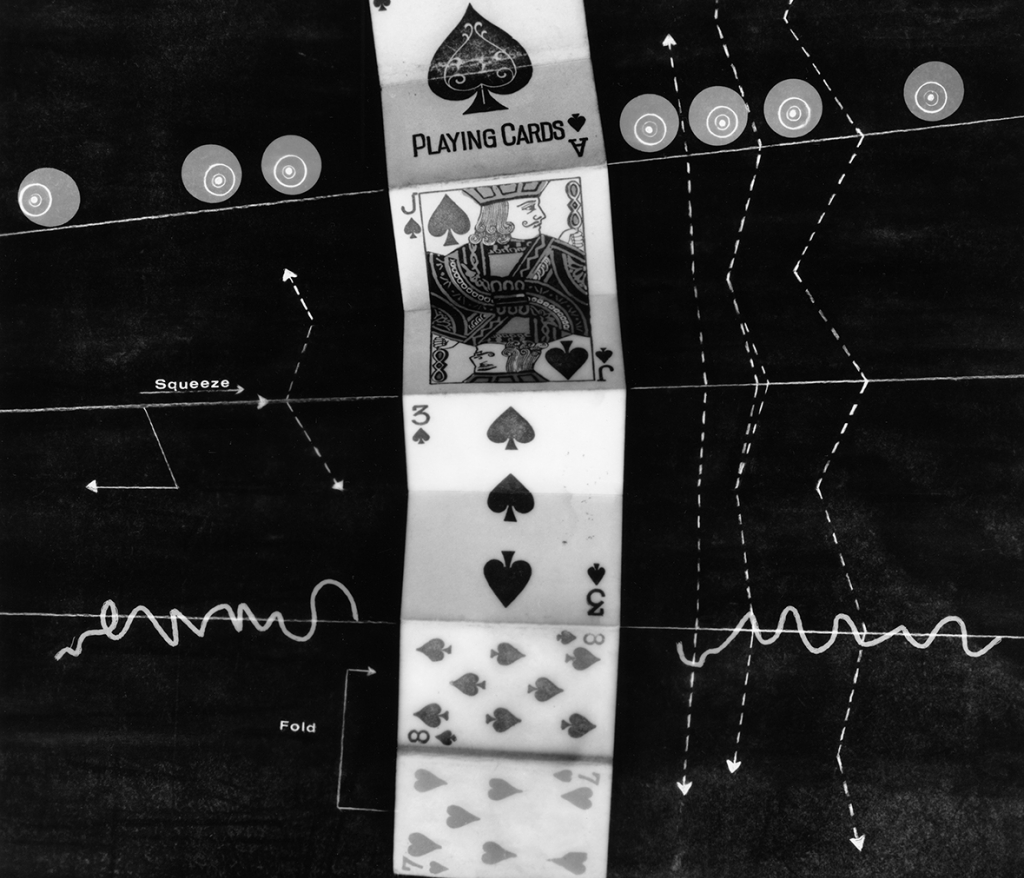

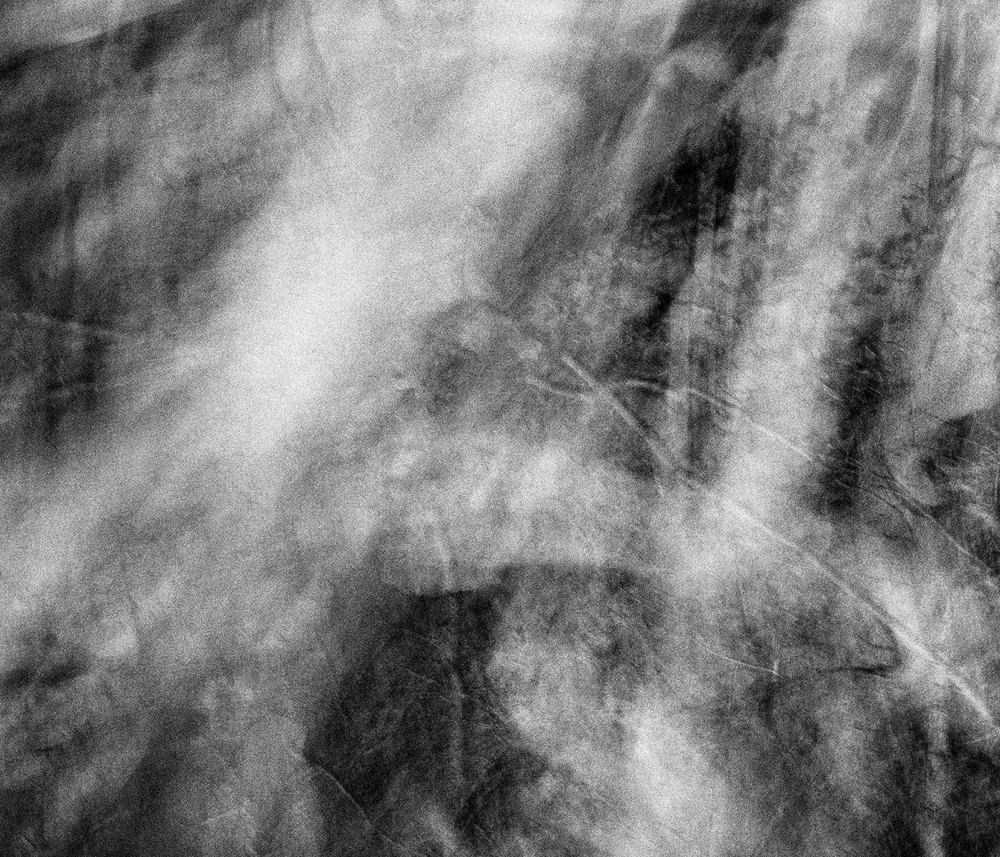

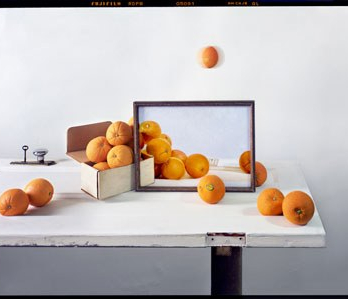

The images are intertwined with the negatives from my paternal side, which I submerged in the water along the route that my ancestors travelled, allowing the sea to corrode the dye; and the negative from my maternal side, I placed under my shoes and walked in their footsteps, abrading and imprinting them with local earth. The natural exposure and the imposed decay are a metaphor for the little connection I have with these places.

Patrick Wack was born in Cannes, France in 1979. Wack is a freelance portraiture, documentary and commercial photographer working in China from 2006 to 2017. His work has been exhibited in Shanghai, Beijing, Berlin, Singapore, Paris and Bordeaux. His commercial clients include : Louis Vuitton, Adidas, The North Face, Nike, Finnair, Suez Environment, Volkswagen Group, Allianz, Bentley, Hermes, L’Oreal and IKEA. Wack has been published (among others) in the NYT, Sunday Times, The Monocle, The Good Life, Nat Geo (China), Vanity Fair and Travel & Leisure. He is represented in Shanghai by the Art+ Gallery and in Berlin and Singapore by MO-Industries.

Out West | Artist Statement

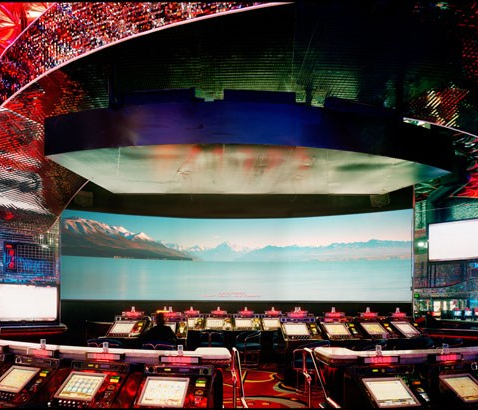

Borrowing from romanticized notions of the American frontier, synonymous with ideals of exploration and expansion, photographer Patrick Wack captures a visual narrative of China’s westernmost region—Xinjiang. Whereas the American West conjures images of cowboys and pioneers, of manifest destiny and individualistic freedom, the Chinese West has not yet been so defined. It is a place of pluralities—of haunting, expansive landscapes, of rough mountains and vivid lakes, of new construction and oil fields, of abandoned structures in decaying towns, of devout faith and calls to prayer, of silence and maligned minorities, of opportunity and uncertain futures. It is a land of shifting identity. In essence, Xinjiang is the new frontier to be conquered and pondered.Literally translating to “new frontier” in Chinese, Xinjiang is a land apart, and has been so for centuries. More than twice the land area of France with a population less than the city of Shanghai, the Chinese province of Xinjiang once connected China to Central Asia and Europe as the first leg of the ancient Silk Road. Yet it remains physically, culturally, and politically distinct, an otherness within modern China. Its infinite sense of space; its flowing Arabic scripts and mosque-filled cityscapes; its designation as an autonomous region; and simmering beneath, its uneasy relationship with the encroaching, imposing, surveilling East. For China’s ethnic Han majority, Xinjiang is once again the new frontier, to be awakened for Beijing’s new Silk Road—China’s own manifest destiny—with the promise of prosperity in its plentiful oil fields.For Patrick Wack, Out West is as a much a story of the region as it is his own, as much a documentation of a contemporary and historical place as it is an emotional journey of what it means to strive, and for what. There exists an inherent fascination in the region—as both key and foil to the new China—and a siren’s call to its vast limitlessness that instinctively incites introspection and desire. Showcasing a romanticism of the frontier, Out West presents Xinjiang via the lens of its present day, in photography that speaks of the surrealistic tranquility—and disquiet—of the unknown. Out West offers an experience of Xinjiang that highlights its estrangement from contemporary perceptions of the new China, accentuating undercurrents of tension and the mystique it has cultivated—whether in their minds or ours. At its core, Out West is a question of perspective: What is the West but the East to another?

Kurt Tong + Patrick Wack

In their respective projects, roaming particular regions within China, both Patrick Wack and Kurt Tong work through the complicated facets of their own capacity to romanticize the land. The photographic stories they produce benefit from their introspective efforts. Both artists display candor as they grapple with the responsibility of representing a particular place, even as they struggle to know and understand the regions that have called to their imaginations.

For Tong, the call came from the desire to connect with his motherland. For Wack, the call came from the modern day frontier. Anticipating the adventure of the outer limits, Wack set out to explore Xinjiang, China’s westernmost region. He deftly documented the many faces of the natural and cultural landscapes of the region. Wack’s image of an old armchair and makeshift table, abandoned in front of a majestic wilderness, seems to be channelling Richard Misrach’s work without even knowing it. His palette of sand and oil conjure the aesthetics of the American western tradition. Wack uses the act of the photographic search as a metaphor for himself as well. He describes the process as an emotional journey “of what it means to strive, and for what.”

Both projects search for cultural identity, and they both acknowledge an inability to create a clean and tidy box from what they’ve found. Looking to his ancestral roots, Kurt Tong returned to his motherland to the cities of Zhongshan and Guangzhou, where his ancestors lived and worked. He came to the project, his mind pre-loaded with nostalgic images, in search of connection and a place of belonging.

In ‘Chongqing III’, at the left side of the frame, a solitary man walks down a bit of dirt road with hands folded behind his back, and a highway overhead. To his right, there is a fragment of what we imagine to be the old, traditional city. Although now dilapidated, it carries echoes of a poetic and pastoral past. In front of the man spreads a horizon of modern city buildings, which look equally worn. To which world does the man belong? His presence on the road that straddles these two spheres is a question mark, as Tong does not reveal where he is coming from or where he is going. Perhaps this man’s life, like Tong’s, exists not in one place or the other, but somewhere in between the two.

Photography is captivating in the sense of reality that it conveys. A picture so instantly places the viewer in the world of the photograph, often without much awareness that the artist’s hand is shaping and filtering what is seen. When we first saw these bodies of work, we knew that they were perfect for Pictura’s inaugural opening at its new home in the FAR Center for Contemporary Arts. Both projects transport the viewer and communicate aesthetically and emotionally about the places they depict. They exemplify qualities that makes the photographic medium so particularly powerful, a rich combination of immediacy, subtle narrative, and beauty.

Born in Hong Kong in 1977, Kurt Tong became a full-time photographer in 2003. He was the winner of the Luis Valtuena International Humanitarian Photography Award and has worked for a number of other NGOs. He gained his Masters in documentary photography at the LCC in 2006 and began working on more personal projects exploring his Chinese roots and understanding of his motherland. A monograph of ‘In Case it Rains in Heaven’ exploring the practice of Chinese funeral offerings, was published by Kehrer Verlag in 2011.Tong’s project ‘The Queen, The Chairman and I’ has been exhibited across 4 continents, including the Victoria Museum in Liverpool, UK; Galleri Image in Denmark; the Visual Art Center at the Chinese Cultural Foundation of San Francisco, Impressions Gallery in Bradford and will be traveling to Lianzhou Photography Museum in 2018.‘Combing for Ice and Jade’, a love letter to the artist’s nanny, one of the few remaining self combed women (Chinese women who pledged never to marry) in the world, has won him the WMA and the Punctum award at Lianzhou Foto. The installation was recently shown at the Himalayas Museum in Shanghai and will be travelling to the Zhongshan Museum of Art in 2018. He is represented by Jen Bekman Gallery in New York, The Photographer’s Gallery in London.

Sweet Water, Bitter Earth | Artist Statement

Chinese in Hong Kong, in Taiwan, and overseas often struggle with their Chinese identity, many have an idealized image of what the motherland is like, whether it’s from stories retold by our relatives, from a romanticized view of a movie. The reality is often very different, especially given the accelerated speed at which China is changing. It is often this failure to meet our expectations and the vast, often unexpected difference in cultures that alienate us from feeling comfortable and secure with our roots.

My paternal ancestral line has strong affiliation with the sea, as fisherman, as deckhands, as traders, marine tragedies also wiped out entire arms of the family. My maternal ancestral line on the other hand, has strong affiliation with the land, as landlords, as builders.

However, while trying to photograph these two cities, I realized how little connection I have with either of these places, emotionally or physically. I realized that my own vision of china was also shaped by TV shows of my childhood and more recently, photographic projects made in China.

I went further into China in search of my own preconceived images of China.

I traveled to all corners of the vast country, trying to find my own connection with my supposed motherland. I found a strange sense of belonging and emotional tide to the landscapes, however, as I got closer to the people, I felt disconnected and alienated. I realized that it is modern day China and its people that I don’t understand and my dream of redemption and return to a lost homeland is ultimately, a failure.

The images are intertwined with the negatives from my paternal side, which I submerged in the water along the route that my ancestors travelled, allowing the sea to corrode the dye; and the negative from my maternal side, I placed under my shoes and walked in their footsteps, abrading and imprinting them with local earth. The natural exposure and the imposed decay are a metaphor for the little connection I have with these places.

Patrick Wack was born in Cannes, France in 1979. Wack is a freelance portraiture, documentary and commercial photographer working in China from 2006 to 2017. His work has been exhibited in Shanghai, Beijing, Berlin, Singapore, Paris and Bordeaux. His commercial clients include : Louis Vuitton, Adidas, The North Face, Nike, Finnair, Suez Environment, Volkswagen Group, Allianz, Bentley, Hermes, L’Oreal and IKEA. Wack has been published (among others) in the NYT, Sunday Times, The Monocle, The Good Life, Nat Geo (China), Vanity Fair and Travel & Leisure. He is represented in Shanghai by the Art+ Gallery and in Berlin and Singapore by MO-Industries.

Out West | Artist Statement

Borrowing from romanticized notions of the American frontier, synonymous with ideals of exploration and expansion, photographer Patrick Wack captures a visual narrative of China’s westernmost region—Xinjiang. Whereas the American West conjures images of cowboys and pioneers, of manifest destiny and individualistic freedom, the Chinese West has not yet been so defined. It is a place of pluralities—of haunting, expansive landscapes, of rough mountains and vivid lakes, of new construction and oil fields, of abandoned structures in decaying towns, of devout faith and calls to prayer, of silence and maligned minorities, of opportunity and uncertain futures. It is a land of shifting identity. In essence, Xinjiang is the new frontier to be conquered and pondered.Literally translating to “new frontier” in Chinese, Xinjiang is a land apart, and has been so for centuries. More than twice the land area of France with a population less than the city of Shanghai, the Chinese province of Xinjiang once connected China to Central Asia and Europe as the first leg of the ancient Silk Road. Yet it remains physically, culturally, and politically distinct, an otherness within modern China. Its infinite sense of space; its flowing Arabic scripts and mosque-filled cityscapes; its designation as an autonomous region; and simmering beneath, its uneasy relationship with the encroaching, imposing, surveilling East. For China’s ethnic Han majority, Xinjiang is once again the new frontier, to be awakened for Beijing’s new Silk Road—China’s own manifest destiny—with the promise of prosperity in its plentiful oil fields.For Patrick Wack, Out West is as a much a story of the region as it is his own, as much a documentation of a contemporary and historical place as it is an emotional journey of what it means to strive, and for what. There exists an inherent fascination in the region—as both key and foil to the new China—and a siren’s call to its vast limitlessness that instinctively incites introspection and desire. Showcasing a romanticism of the frontier, Out West presents Xinjiang via the lens of its present day, in photography that speaks of the surrealistic tranquility—and disquiet—of the unknown. Out West offers an experience of Xinjiang that highlights its estrangement from contemporary perceptions of the new China, accentuating undercurrents of tension and the mystique it has cultivated—whether in their minds or ours. At its core, Out West is a question of perspective: What is the West but the East to another?